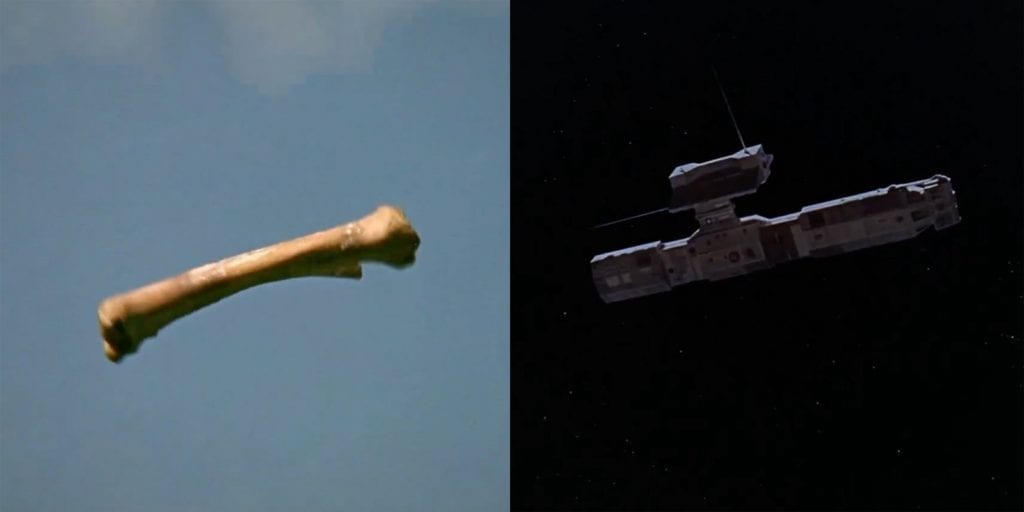

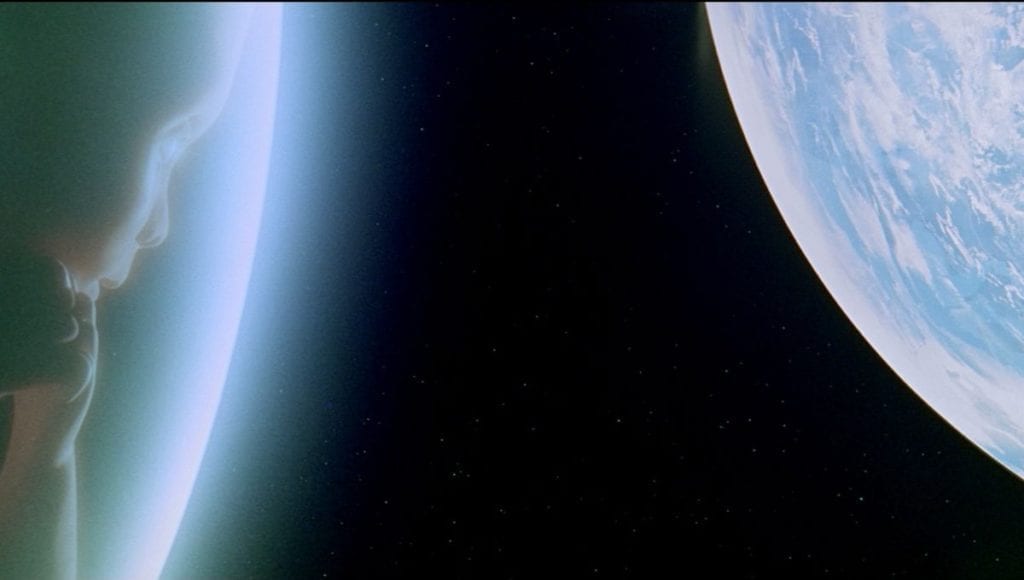

Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey confounded its first audience more than 50 years ago, yet somehow the film still feels like a countdown towards tomorrow. Technological advancement is the defining impetus of the modern era, and so the relevancy of sci-fi films often seems to have an expiration date. Reality exposes cinematic futurism as outdated — even naive — in the face of the latest innovation. But 2001 endures its own experiment: the test of time. With beautifully manufactured scenes, Kubrick takes his viewers from pre-historia to interstellar oblivion with a segmented storyline that jolts through time and space. An ominous black monolith of alien origin bridges this chronology, and Kubrick fronts an enticing treatise about the enigmas of human progress.

The intellectual – even literary – content of 2001 has the potential to overshadow the film’s aesthetic value, but the design elements that Kubrick employs are calculated and deliberate in a way that drives forward his predominant thesis. Kubrick’s worldview is that of a cynical observer, if not a prophetic one. He enlists the same capital and commercial institutions that he deems destructive to persuade his audience. This sense of intimate familiarity with the rise and fall of empires becomes all the more convincing when the viewer can recognize, relate to, or at least envision themselves and the world they live in on the screen. To say he parodies these institutions may be an overstatement, but 2001 spends a great deal of time alluding to the dystopia that is Western cultural “progress.” Kubrick’s futurism is not an attempt to grasp the impossible or unimaginable, but rather to present a cogent picture of the very near, the eventual, and the impending.

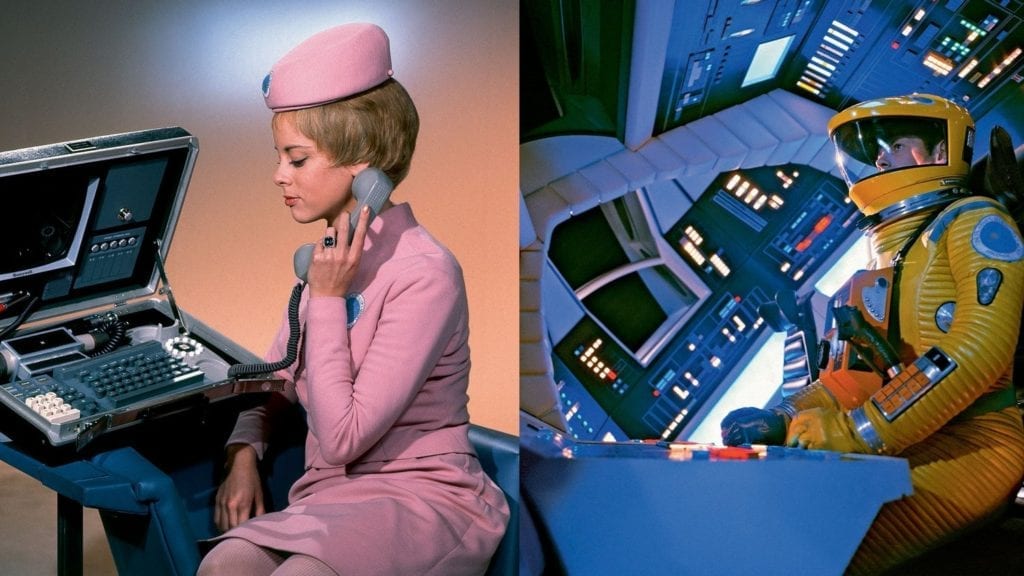

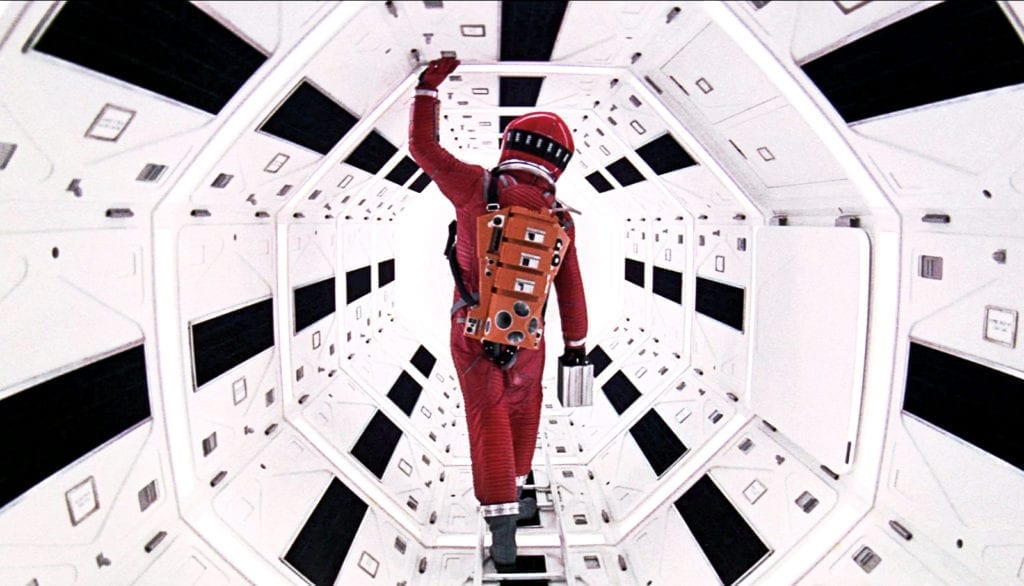

For 2001 Kubrick employed Savile Row designer Hardy Amies whose eponymous brand in the 60s was at once a traditional powerhouse and a forward-thinking treatise. Amies’ role in Kubrick’s film proves far more than that of a costume designer, and the two artistic visionaries clearly work in tandem to develop the film’s contentious thematic content. With a succession from trim-suited executives to the metallic blues, yellows, reds of the spacesuits––taking the viewer from fortune-500 America to the swinging sixties––Amies successfully enhances Kubrick’s interplay between fantasy and reality, progress and regression, control and the unimaginable.

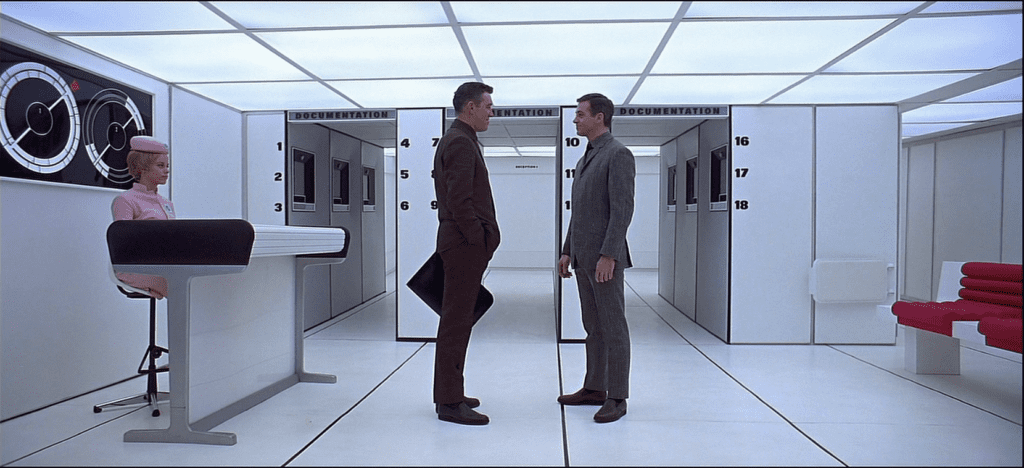

Best known as the official dressmaker of Queen Elizabeth II, Amies was ostensibly a contradictory choice on Kubrick’s part. The unchecked cinematic experimentation that is 2001 is a far cry from the traditional neatness of English gentlemen types. Where the two converge, however, is at the center of Kubrick’s masterpiece: timelessness. Both designer and director gravitate towards the understated; themes, colors, and patterns that could pair against any backdrop, whether that be in the city or on a spaceship, the 60s or at the turn of the century. Amies’ sketches for the film––the executive’s tweed suits, the stewardesses’ sugar-pink uniforms, and the astronauts’ utility ensembles––were all done in a simple square cuts, block colors, and outré details. These drafts translate almost identically to the screen and are central to giving the film its timeless futurism.

When one considers Kubrick’s obsession with symmetry and color composition, as well as his meticulous attention to detail, his pairing with Amies makes sense. With his rigorous and traditional training, Amies understood the tension between what was current, fleeting, and what was eternal. The Pan Am space crew of 2001 echoes the ‘60s space-age visions of André Courreges and Pierre Cardin with their mod-inspired uniforms, but their costumes also exude a certain conservatism that makes Bowman’s character still feel futuristic to the contemporary audience.

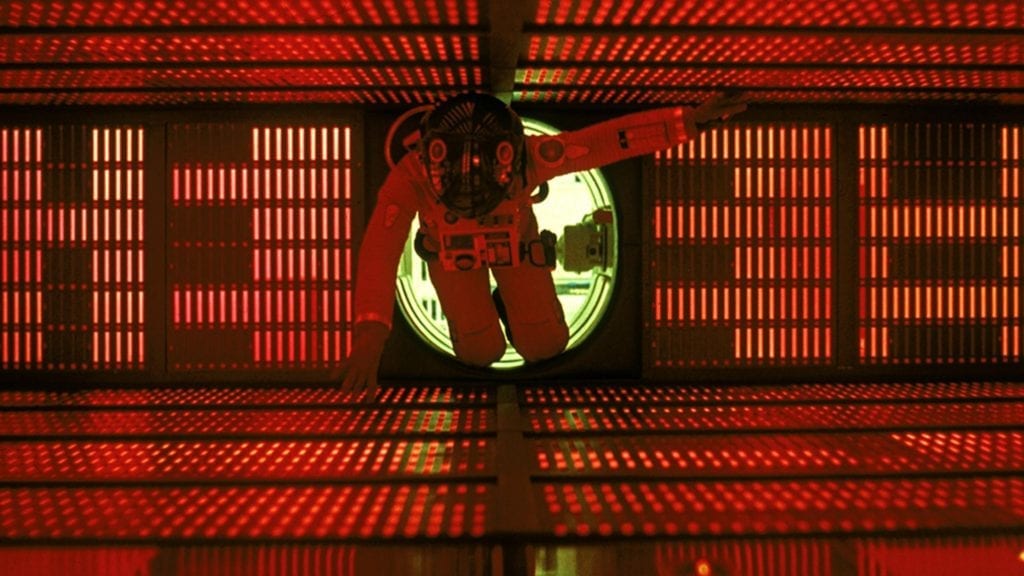

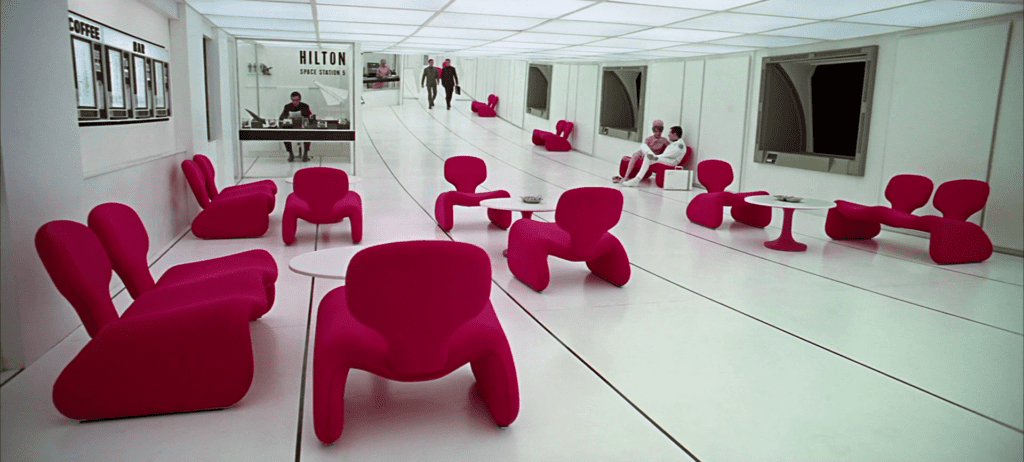

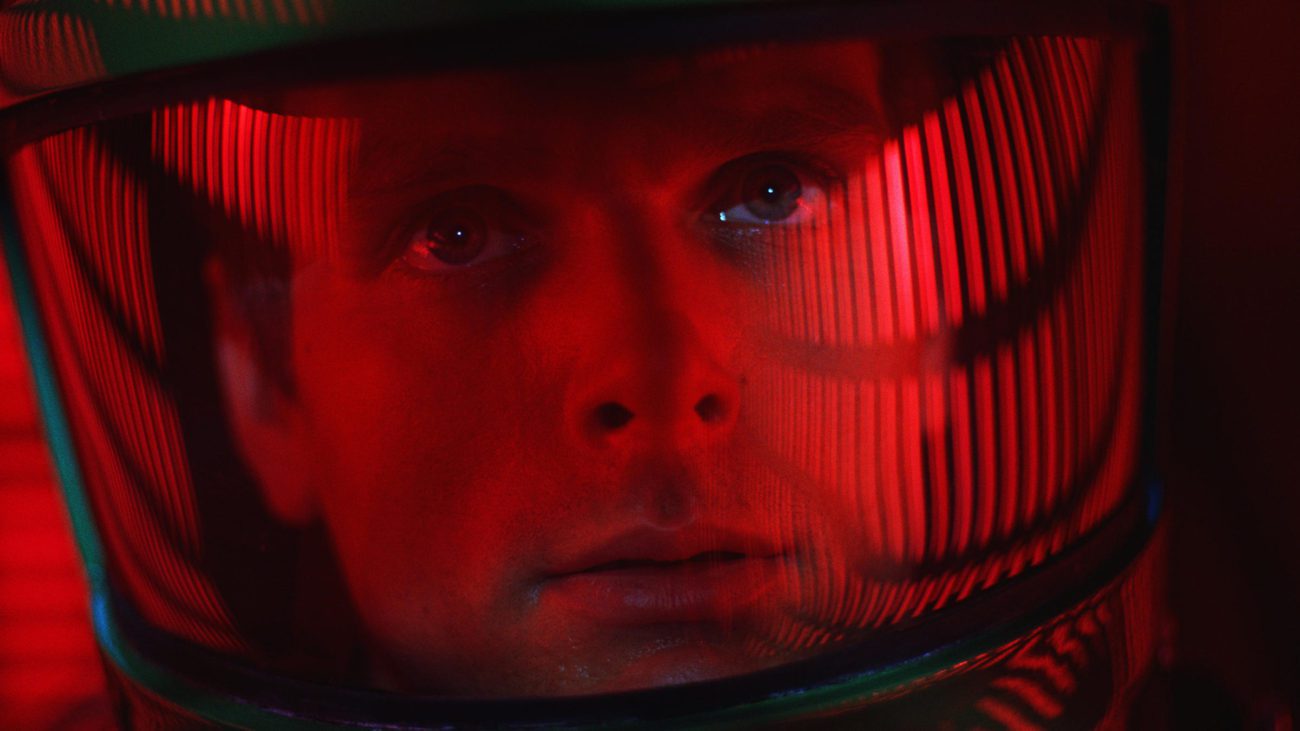

Kubrick is fixated on red. From the Djinn chairs of the space station HAL 9000’s omniscient eye, red penetrates the scenic atmosphere of 2001. Designed by Oliver Mourgue (while working for French manufacturer Airborne International), the Djinn chairs embody a temporal futurism with their wave-like and low-slung silhouettes. Juxtaposed against the white walls and floor, these iconic pieces of furniture demand attention, appearing like flecks of blood against a white backdrop, in the same color that seems to punctuate some of the film’s most striking scenes. Red is an evocative tone; encouraging reactions of fear, of passion, of urgency, and of masculinity. Kubrick suggests its underlying connection to the human psyche in 2001. With a highly calculated aesthetic palette, the director enhances the film’s commentary on human consciousness, emotions, and the nature of man.

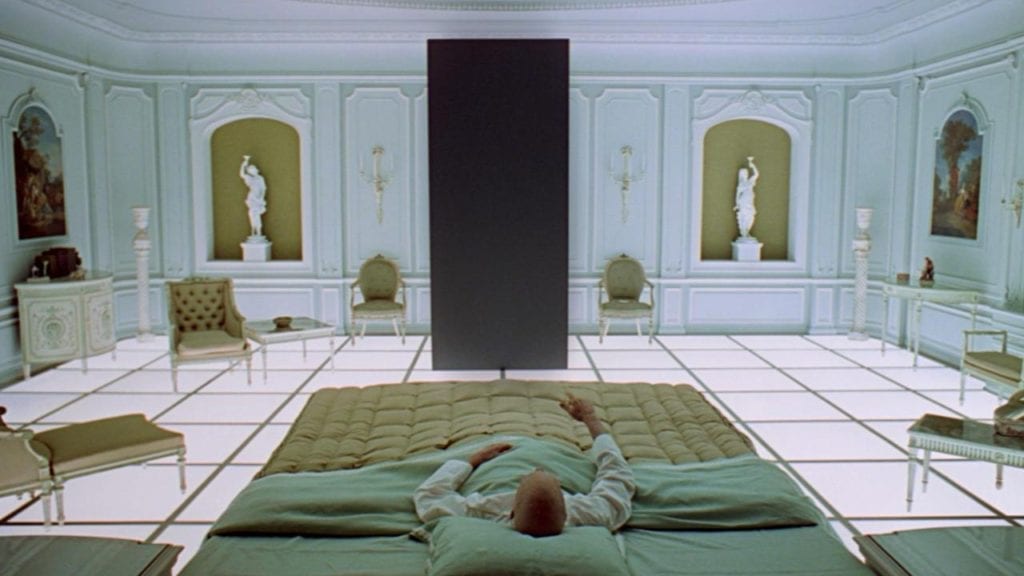

It was production designer Tony Masters who worked with Kubrick to envisage the “bedroom at the end of the universe” where Bowman spends the rest of his life before his famous “starchild” rebirth. Unlike other interiors of the film, these final scenes do not take place against purely futuristic backgrounds. Rather, the space is a melding of time periods — a Louis XVI-era French bedroom illuminated by stark, fluorescent lights. Renaissance portraits adorn the walls and place Bowman in the heart of the mid-1700s, and perhaps Kubrick alludes to Bowman’s impending rebirth as similar to that of humanity at the turn of the 18thcentury. The unexpectedness of this architectural transition is consistent with Kubrick’s style. With abrupt temporal leaps that bridge eons and languorous moments that seem endless, time is malleable in 2001. In this way, aesthetic composition allows Kubrick yet another outlet to further his thesis on time and human history. What was true then is true now, he reminds.

In the same way that 2001 delivers a social commentary on technological and anthropological evolution, Kubrick’s film also set new standards for cinematic innovation. In his fastidious attention to detail, Kubrick introduced strategic product placement into the world of cinema. He invited commercial product manufacturers from Nikon and Kodak, to Hamilton watches, to Dupont fabrics. Even Macy’s and Hilton Hotels were included in the catalog. An advertising opportunity sure, but Kubrick enlisted these architects and commercial companies to venture future projects; to test how their products would look decades later. 2001 was a revolutionary film, and anyone who has experienced the three-hour tour de force can attest to its splendor. But to the aesthetic eye, Kubrick’s Space Odyssey was instrumental in providing a cinematic canvas for progressive design.

" alt="">

" alt="">