Against the quiet, monochrome backdrop of a Colorado winter, every movement, every voice, and every color in The Shining echos with narrative meaning. A thriller about madness, delirious isolation, and masculinity, the film speaks to Kubrick’s attention to detail as well as his attentive use of foreshadowing, symbolism, and allegory. The film bleeds with cinematic detail, generating a subtle, yet horrific, vibrational quality throughout the Overlook Hotel.

Kubrick’s aesthetic composition lends itself to particularly literary modi. However, Kubrickian cinema does not suppose “literature” to mean language as a medium for narrative. In fact, the dialogue is often entirely absent from his scenes. Themes, critique, and plot motivation operate subtly, and their accessibility relies largely on mise en scéne. This sort of cinematic opus requires an extremely meticulous director, and Kubrick (without contention) plays his role perfectly.

Perhaps the most operative device in Kubrick’s toolbox is leitmotif. Derivative of the German leitmotiv meaning “leading” or “guiding” motif, the term was originally used to characterize a short, constantly recurring musical phrase. However, its application can be further generalized to mean the smallest structural unit possessing thematic identity. Analyzing color as leitmotif in The Shining highlights Kubrick’s ability to translate literary commentary onto the screen. Kubrick wields his color palette to parallel Jack’s psychological degradation, to chronologize spatiotemporal divisions, and even to lampoon the social institutions that foundation the entire film.

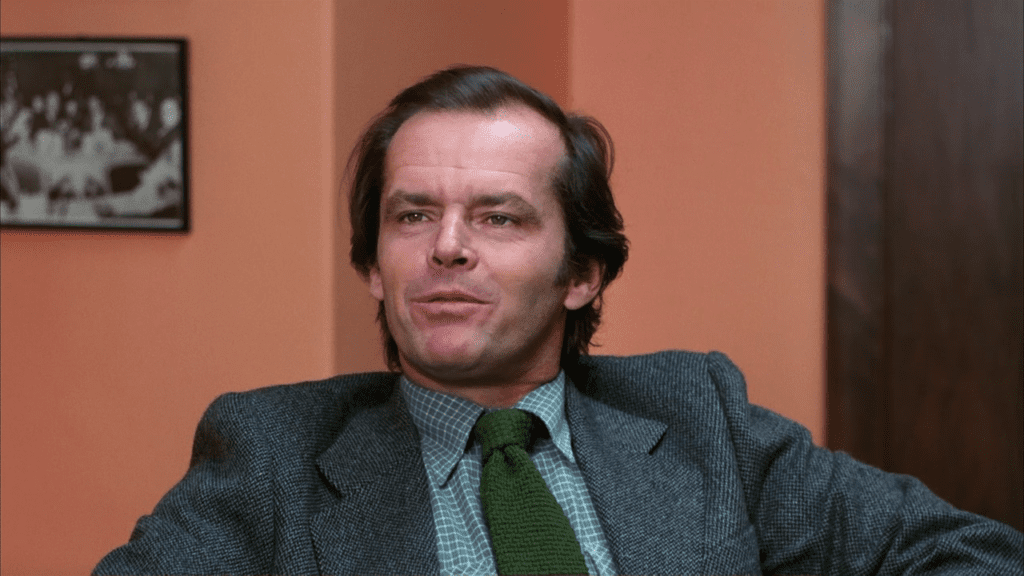

The Shining certainly proves that suspense and predictability are not mutually exclusive. Even to the viewer without any prior knowledge of the seminal plot, the foreshadowing of Jack’s impending madness during his interview with Mr. Ullman is amusingly overt. Much of this can be attributed to the scene’s overly-suggestive dialogue, but what is also interesting is the subtle stylistic nod Kubrick makes at the film’s ending. Mr. Ullman’s office shocks us with its tastelessly bright coral walls, and Jack’s forest green tie and grey jacket immediately provide a striking contrast in their mundanity. For the first half of the film, Jack wears a similar shade of green in every shot, and “greenness” can easily be attributed to immaturity in relation to the Overlook’s daunting history. Interesting still is how Kubrick preemptively taunts his doomed protagonist with the dramatically ironic shade, as foresight immediately relates Jack’s green ensembles to his eventual deathbed: the hedge maze.

In a concurrent scene, Jack’s wife and child sit at home around the breakfast table. Wendy is youthfully dressed to the point of foolishness in a blue dress layered on top of a bright red blouse and boots. Redemption is granted endearingly, as her son Danny’s clothing mirrors her own. However, after hearing the news of his father’s new job and the family’s imminent move to the Overlook, Danny suffers a seizure in reaction to a clairvoyant episode. Blood spills into a red-walled room while a set of twins dressed in their blue Sunday’s best stare blankly into the camera lens. Immediately, Kubrick encourages a dual significance behind the blues and reds that will continue to penetrate his scenes. Signifiers for youthfulness and domesticity are immediately juxtaposed against a similarly-palleted backdrop of death and psychological horror.

Kubrick also manages to explore a foil relationship between Jack and his son using red as leitmotif. Having already established a symbolic binary with the shade––signifying both youthfulness and death––Kubrick extends this metaphor to equate innocence with madness. Danny continues to wear red throughout the film, while objects and scenic elements associated with him maintain a similar tone. Although eerie, the brightness of Danny’s red clothing highlights his childishness, and, more importantly, his vitality. Kubrick develops an interesting interplay between red and green upon the Torrance family’s arrival. Danny and Wendy still wear red, and Jack green. It’s a comforting juxtaposition, as the natural green environment (and Jack’s sanity) are of no threat to Wendy and Danny’s life and youthfulness. However, when winter arrives, Danny is placed against a white background. Death surrounds the Overlook Hotel in ominous monochromacy, and the boy’s blood-red jacket stains the landscape.

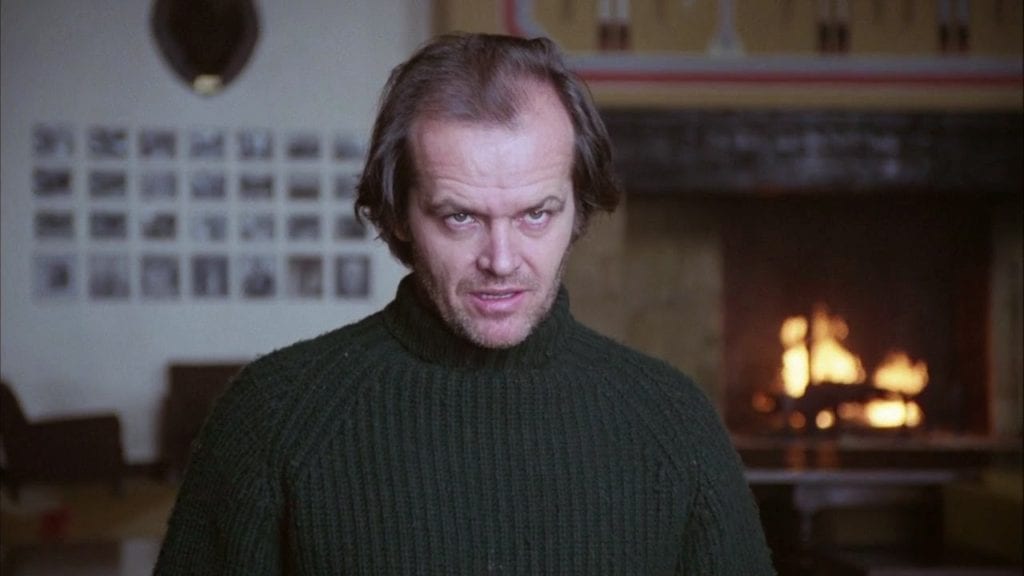

In the first weeks, Jack’s green sweaters continue to highlight the disparity between him and the hotel. The coral walls of the first scene bleed red in the waning light. They loom over Jack’s hunched figure at his typewriter, and their grandeur mock his attempts to write. It is in this study that his sanity begins to deteriorate, becoming increasingly frustrated at his inability to write. When Wendy finally reads his pages––the notorious “All work and no play makes Jacky a dull boy” ––it’s too late. Jack has substituted his green athleisure uniform for his famous maroon bomber.

It is at this climax that Kubrick establishes the morbid relationship between Jack’s madness and his son’s innocence. In his impotence, Jack longs for the creativity of a child. He admires Danny’s childish gaze, who in his clairvoyance, can foresee what is to come. The boy’s psychological arc is a dynamic one and the viewer is made aware of its activity. Jack, however, is unable to access a similar vision. He is plagued by time and a lack of creativity, and in turn retreats to childish language when he eventually puts words on the page. But the price is fatal, as illustrated by the much deeper, much more morose shade of red that he wears during his psychotic break. He mirrors Danny in such a way that their roles are reversed, and Kubrick perversely exchanges clarity for insanity.

Using The Shining’s cyclical chronology, Kubrick exposes a profound failure in the American consciousness, revealing the ways in which historical tragedy, neglected in the national memory, haunts the modern world. In the same way that Kubrick traces Jack’s psychological degeneration, he also includes an allegorical dialogue about social madness, senselessness, and reminiscence. Racism, classism, and breach of the nuclear family are presented as indictments of American values, and Kubrick enlists a catalogue of Americana emblems to lampoon the deterioration of the national psyche at its own expense.

The Overlook Hotel sits on a Native burial ground. By including this detail Kubrick immediately forces his viewer to recognize the role of memory in his film. A symbol of white bourgeois opulence, the hotel stands mockingly over its native origins, and the Torrance family find themselves trapped in a tangible, quasi-recreation of American history. When the indicative greens and lusciousness of the Colorado mountains are cloaked in snow, Kubrick isolates the Torrance family and puts the modern American ideal on trial. Blues and reds are now also indicative of the national flag and, plagued by insanity, completely disavow the constitutive standards of the American dream, the nuclear family, and national stability. It must be observed that Room 237––the nucleus of the hotel’s gruesome past––shocks the viewer with its green walls and purple floors. It stands in such contrast the rest of the characters and set that Kubrick seems to parody the fecklessness of American ideals; faced with a milieu of immovable history, these emblems and symbolism of national patriotism are not only volatile and frail, but easily subject to complete annihilation.

Kubrick indulges his proclivity for using mirrors as cinematic devices in The Shining, submitting that the film is horrific not because it’s about ghosts, but because it reflects its audience as Americans. Past, future, and the present are intimately and concurrently yoked under a single narrative, and Kubrick forces his viewer not only to remember a debilitating past, but to understand its implications on the modern condition, the American condition. If we forget our origins, or at least believe a blind fiction that July 4th, the American dream, and the stability and rationality of our values function within a vacuum, we too will meet the fate of “Johnnyyy.”

" alt="">

" alt="">