“Reynolds has made my dreams come true, and I have given him what he desires most in return,” says Alma (played by Vicky Krieps) in the first line of the film. Such a romantic sentiment is followed by the inquiry “and what’s that?” to which she answers…“Every piece of me.”

…

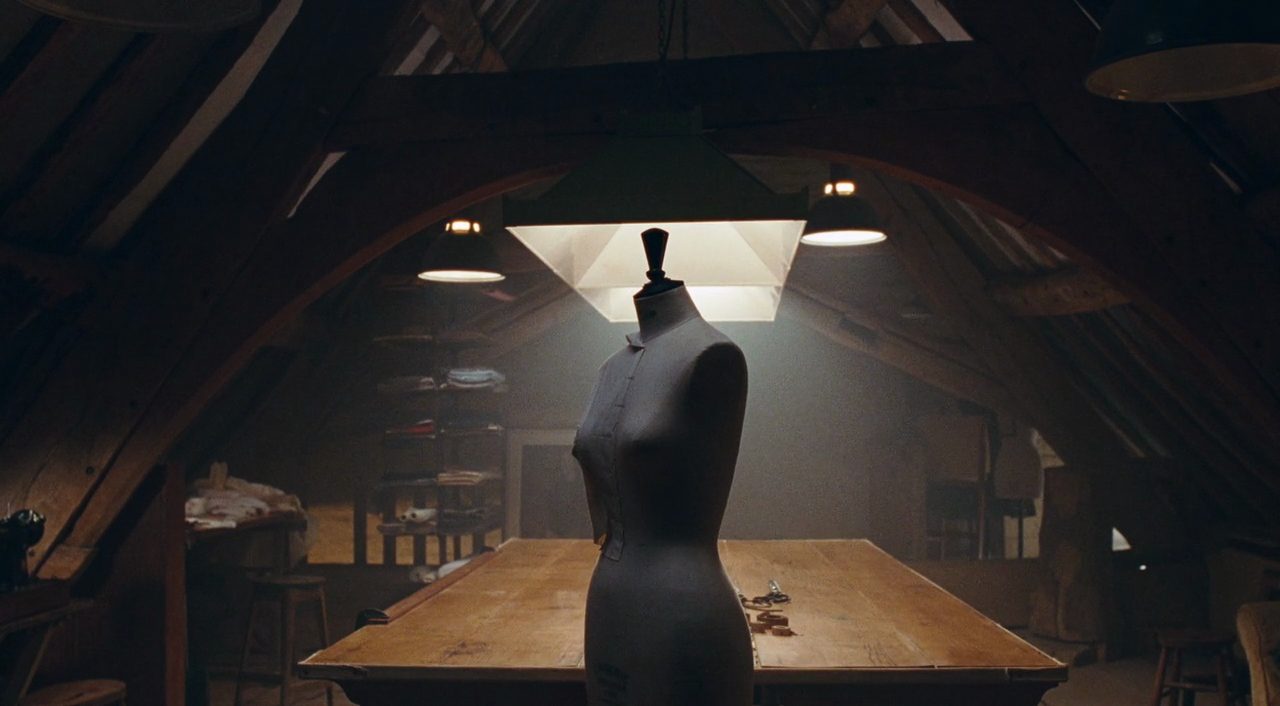

Paul Thomas Anderson’s beautiful and bizarre Phantom Thread tells the story of lovers unable to give and receive as equals in a relationship with an unstable power dynamic. The couple re-captures their initial spark and cements their commitment through a mutually destructive balancing act in this darkly twisted fairy tale. Reynolds Woodcock (Daniel Day-Lewis), a haute couture dress designer, is sought after by the sartorial tastemakers of 1950’s London. Woodcock’s art is so all-consuming that he appears at first to be incapable of giving himself to anyone emotionally. He even states that marriage would be impossible for him because of his art.

But, he is smitten-at-first-sight when he encounters a beautiful waitress in the country, Alma. He whisks her away from her simple life, like Cinderella, into his world of high-fashion. Reynolds installs Alma in the House of Woodcock’s posh upper echelon glamour as his model, muse, and the apple of his eye. The romance quickly warps to Reynolds whims as a demanding, petulant artist. Alma, as live-in mistress, is a guest in his elite fashion house, a power imbalance which puts her at his mercy. As his favorite and muse, Alma is first-lady of the London fashion scene – where her lover’s job is to intimately dress and create for an endless parade of wealthy, beautiful patrons.

Dazzling couture and cutting emotional performances carve a deep, demented love story out of the familiar “rescued by Prince Charming” trope. The story unfolds amidst sumptuous visuals and exquisite mid-century ball gowns to lay bare an ever more ominous romance. Phantom Thread is an odd, bacchanalian celebration of beauty and desire, sparkling like a dark gothic gem. The cinematography is poetically gorgeous, banking on gem-tones and Rembrandt-esque shots of contrasting light and dark. The story of a lonely artist who finds a beautiful muse who understands him as both man and artist is the basis of the fairy tale. Alma, finds that as the object of her lover’s affection, there is no room for her own voice or opinions. The fantasy quickly crumbles to reveal that she lives the dream only at his behest. Their love is desperate and tender on both ends, and embraces the morbid and grotesque side of human emotion; celebrating it as the savior of their romance. Phantom Thread paints the toxic nature of a deep, dark love tinged with the dangerous side of desire. It is a love story of mutual destruction and escapism on the edge of romance.

Three-time Oscar winner Day-Lewis, plays Woodcock with such an earnest intensity and passion, he does the role and his illustrious acting career justice in his final film performance. Woodcock is a perfectionist, a workaholic, and a slightly tyrannical artist who vowed to never marry. He describes being an artist and married as mutually exclusive. “I’m a dressmaker,” he says matter of factly when asked why he’s so adamant he will never marry.

The first glimpse of the artist at work is of Woodcock sketching intently at the breakfast table. Just as the dresses, flower arrangements, décor, and color palettes of the film are shot with striking elegance – enticing meals tantalize the senses throughout the film. The camera lingers seductively on pastries and entrees that look like works of art, just as the camera teases the audience with swaths of lace, satin, and velvet.

His first client is a rich woman named Henrietta, who seemingly glides up the spiral staircase to meet Reynolds. She is a snapshot of the opulence he caters to, and a fitting match for Reynolds’ own gentlemanly decorum, formality, grace, and style. She steps out in his creation – a royal purple, velvet-caped gown fit for a queen. Taking her in his arms with noticeable familiarity and questionable intimacy she exclaims “yes!” He clasps her hand in his and she proclaims the dress, “worthy of everything we have been through.” Adding meaningfully, “it will give me courage.”

It is in this scene that we see Reynold’s sensitivity and depth, as can only be communicated through his art. He is full of emotion, and his art is created and sold as pieces of his heart. In fact, he takes such care with his art as an expression of his feelings and intentions that he is shown sewing messages and good luck talismans into the hems of dresses. He has displayed himself up to this point as walled-off and emotionally unavailable, interpersonally. But via the dresses he makes – his expressions of love are as deep as they are grand. It is through his creations that he is able to speak his heart’s intentions. Reynolds the master artist expresses his affection through his work only – as he appears to be otherwise incapable of intimacy.

In a glimpse of the artist’s love life before he finds Alma, he dismisses his lovers once they reach a certain point of intimacy or overstay their welcome. Reynolds agrees without hesitation, at the nudging of his doting sister Cyril, that it has come time to send his lover away and he immediately changes the subject to his experience of an “unsettled feeling.” He is having dreams and thoughts, he says – of their deceased mother. “I very much hope that she saw the dress tonight, don’t you?” He asks like a hopeful, innocent little boy..

“It’s comforting to think the dead are watching over the living, I don’t find that spooky at all,” he adds.

Haunting classical piano accompanies scenes of Reynolds driving at dusk to the country. The aubergine hued car he drives echoes the purple of the first evening gown he has delivered, and he emerges from the car merlot socks first. The color palette of the film consists of vibrant, rich, gem tones and deeply saturated colors mirrored by his ceations.

He falls for Alma, a beautiful waitress from the country — seemingly at first sight. She wears an unassuming raspberry colored waitress’s uniform. In reality, Day-Lewis insisted that he and Krieps, meet for the very first time in character in this scene. The awkward charm and purity of their first meeting is very real. He proceeds to order almost every item on the menu, including, specifically, raspberry jam. His appetite is for her. This theme recurs throughout the film. She leaves a note on the bill for him, referring to him as “the hungry boy,” and he asks her to dinner that night.

The tactile nature of the fabrics fill the screen with dreamy chiffons and silks, full ball gown skirts, and a charming parade of high fashion. The film is a feast for the eyes. During their first dinner together, Reynolds removes Alma’s lipstick with the precision of a painter by dipping a cloth napkin in water and running it along her lips with his finger. In this act, it’s as if he’s painting her and she has become his work of art. She wears a succulent cherry red dress with white piping details and delicate buttons.

Alma’s jealousy is spurred by Reynold’s creation of a wedding dress for another of his muses, a French princess with whom he has a long and intimate history. Alma’s jealousy reaches a fever pitch during a fitting for the wedding dress during which she introduces herself to the princess as the Lady of the House. She wants to show Reynolds how she loves him, she insists on making him a home-cooked dinner, to express her love for him in her own unique way. Wearing a dress of her own creation during the dinner, she declares her love. Reynolds is avoidant, brusque, petulant, and clearly thrown off by the whole affair being out of his realm of comfort. He does, however, note the dress Alma made for herself – in his first acknowledgment of her being an artist with valid ideas herself.

In one of the most dramatic lovers’ quarrels in the film, he rejects her offer of love (the home-cooked meal), and maintains his condescension, distance, and inaccessibility. She confronts him and accuses him of being on the brink of getting rid of her. This hurts him visibly, and he dramatically lashes out at her and accuses her of going out of her way to ruin his night, perhaps his entire life.

It’s then that Alma resorts to a calculated and cruel act — purposefully poisoning him. She knowingly picks poison mushrooms and feeds them to Reynolds. He becomes so ill that he can’t work, and falls ill while putting the finishing touches on the Princess’s wedding gown the day before it is to be presented. He seems like he may even die, and Alma is there to care for him, and she steps in to direct the seamstresses to make sure the dress is fixed in time. It is only in this state that he is able to be fully vulnerable and reliant on her in a way that is otherwise impossible for him. It is during his initial illness, after having been first poisoned, that the film takes a surrealist turn and he has a hallucination of his mother wearing the first wedding gown he designed. The visions of his mother are superimposed over his view of Alma dutifully waiting on him and nursing him back to health.

He seems to see his mother as the untouchable ideal which no woman can come close to — until he is poisoned, at which point he sees Alma as not only his muse/lover, but as a mother figure, or at least on par with the idealization of his mother. When he awakens the next morning, with the Princess’s finished wedding dress symbolically standing in the foreground, he asks for Alma’s hand in marriage.

When Reynolds finally deduces that Alma is poisoning him, he appears not to be threatened but grateful and relieved. Their love and the balance of power in their relationship is maintained through the intentional poisoning by Alma of Reynolds. Reynolds is able to rely on, trust, and be vulnerable with Alma during his convalescence, in stark contrast to his independent identity as an artist — one that is entirely emotionally impenetrable. Through Reynolds’ self-inflicted injury (vulnerability) he is able to surrender to Alma in a way that is not possible for him as an artist. Through the poisoning the relationship’s balance of power is restored, and their trust and intimacy is deepened. In order for Reynolds to be capable of letting go of complete control, he hurts himself by sacrificing his health to Alma, thereby giving her complete control over him during these poison spells. It is the ultimate act of trust: If she poisons him too much or doesn’t care for him attentively, he could die. This connects and serves as a metaphor for the creative process, which (at least in this film) is an inherent act of narcissism in direct conflict with love.

Reynolds purposely wounds himself in order for Alma to save him, repeatedly, to restore an emotional balance to the relationship. Is there anything more toxically romantic? As visually enchanting as it is unsettling, Phantom Thread is a gothic fairy tale and dark romance which sincerely explores the hearts of artists.

" alt="">

" alt="">