Empire-building, Amy Kaplan argues in “Birth of an Empire,” is an inherently messy project, one that blurs the boundaries between the domestic and the foreign in paradoxical ways. Cinema, one of the central ideological apparatuses of empire, epitomizes this tension: portrayals of American conquests have long projected domestic images and motifs onto foreign settings to make those places feel familiar and worth fighting for. Less examined, however, is empire’s equally troubling tendency to trivialize or ignore the communities and cultures it encounters.

In some cases, the failure to acknowledge foreigners owed as much to limited access and budget as to lack of will. Early films about the Spanish-American War, for example, re-enacted the U.S. invasion of Cuba at home, with toy boats in bathtubs and staged-battles in the New Jersey countryside, simply because getting equipment to Cuba was impractical. Yet, even when actual footage of Cuba could be obtained, it, too, focused on domestic scenes of American soldiers cleaning, cooking, and making camp (Kaplan, 148). Cuban soldiers, although they fought alongside Americans in the war, were relegated to the margins of these films, if shown at all.

Kaplan argues that these early war films show the domestic sphere as “the site from which [empire] is launched” (156). However, in reproducing the domestic sphere on foreign terrain, they also peel back the veneer of America’s “humanitarian” mission to reveal a darker, colonial vision that silences indigenous peoples.

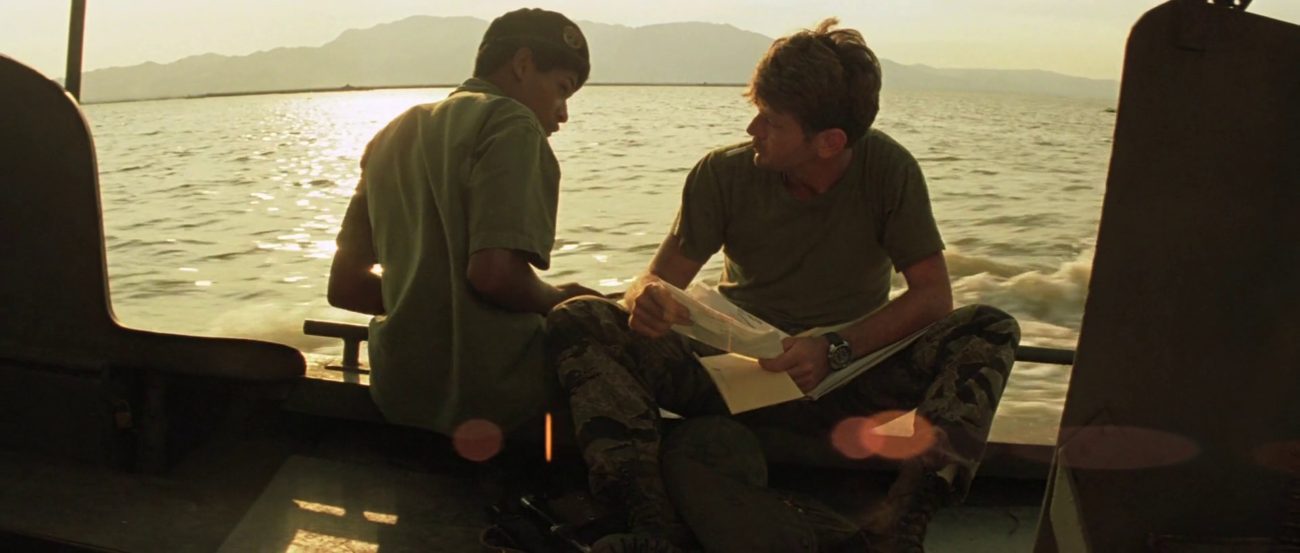

Decades later, when America’s imperial gaze shifted to Southeast Asia, Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979) would employ similar imagery in a critique of the Vietnam War. The film, an adaptation of Joseph Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness” to Vietnam, follows Captain Benjamin Willard (Martin Sheen) on a crusade to kill one of his own, Colonel Walt Kurtz (Marlon Brando), who has supposedly “gone insane.” Ultimately, Coppola’s macabre vision of Kurtz’s camp falls into the same representational traps as early cinema. Despite a large budget, the film reproduces a version of the domestic sphere in Cambodia, which consigns native peoples to the periphery.

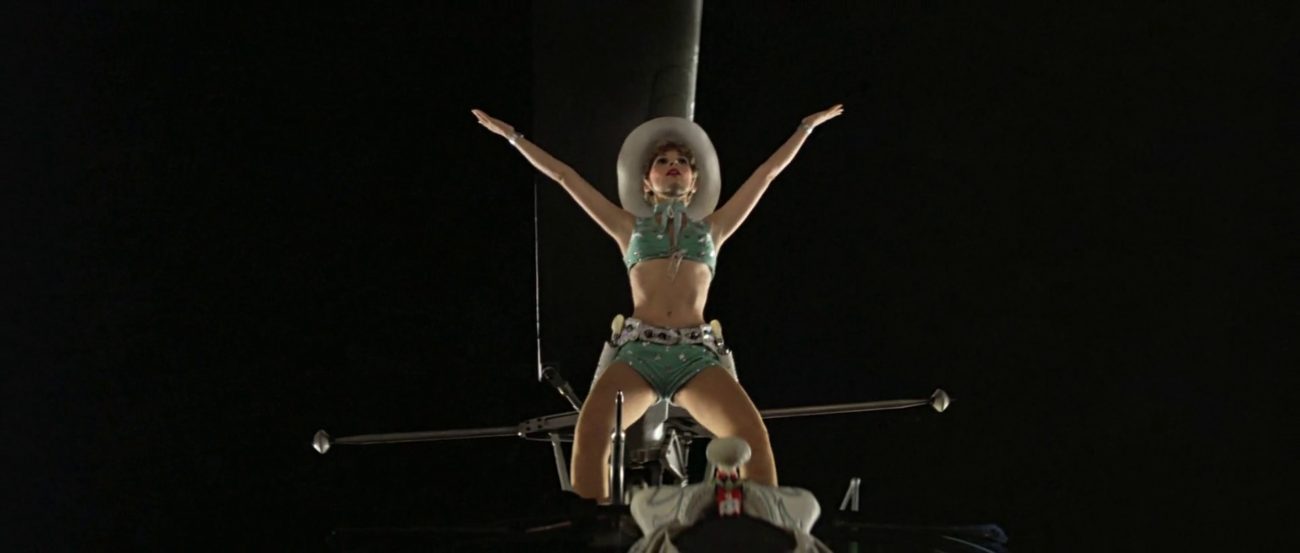

From the moment Willard boards the boat that will take him to Kurtz, the vehicle becomes a site of safety (read: domesticity) from the untamed wild. The boat as a site from which the men both reenact home (tanning, listening to the radio, water skiing, etc.) and conduct their crusade through the jungle already does much to expose the link between domesticity and empire.

However, in the moments before Willard arrives at Kurtz’s camp, Coppola muddles the boundaries between these spheres even further: an image of stone columns, carved with identical faces, is superimposed on a shot of the boat moving through the fictional Nung river. The boat moves between the two faces, whose visages recall a stereotypically oriental architecture. The boat, which previously served as a means of protection throughout their journey (albeit in a limited capacity), is reconfigured here as entering or crossing into the foreign. As the columns expand to contain the boat between them, Coppola collapses the boundary that once separated the soldiers from their “exotic” exterior. The columns, which do not appear in the diegetic story-world until the soldiers arrive at Kurtz’s camp, even threaten the linear narrative, forcing the viewer to consider that the domestic space of the boat is constantly mediated by the presence of the foreign throughout the film.

As the boat nears Kurtz’s camp, an uncanny scene materializes ahead of Willard. Out-of-focus bodies stand watch from the river bank, fires burn impossibly on the water, and smoke billows up from the ruins that make up the camp. Most startling, however, are the rows of men in white war-paint, whose canoes span the width of the river 50 yards from Willard’s boat. Painted head-to-toe in white, the figures appear ghost-like, interchangeable so as to appear “unreal” (Kaplan, 160), and at the same time enact a kind of reverse black-face. Anticipating the arrival of the white soldiers, they “become” white themselves, in a reversal of the way the West subordinates their bodies. In this way, they seem to point a mirror at the soldiers that says, at the end of this journey, all that you’ve found is yourselves.

When the boat approaches the painted men, they subvert our expectations by parting to let him pass, bringing into focus the camp in all its glory. It’s a ridiculous image of crumbling statues and half-buried bodies, almost laughable in the extremes to which it goes to make visible Kurtz’s world of anarchy and destruction. As the boat moves towards the shore, a shot of Lance (Sam Bottoms), his face painted in camouflage-greens and browns, inverts the white war paint of the “natives” as an eerie two-beat strum plays. Coppola’s use of long takes to show Lance in relation to the painted Vietnamese has the effect of suspending normal viewing conventions, destabilizing the logics of “Us and Them.”

When an American photojournalist (Dennis Hopper) appears among the ranks of the hundreds who flank the camp, the film jolts into motion. Chef (Frederic Forrest) turns on the boat’s siren; the “natives” suddenly turn and run; and the American boards the soldiers’ boat, identifying the people fleeing as Kurtz’s children. With the invocation of the natives as “children,” Kurtz is established as a father figure who has abandoned one domestic sphere (the home-front) for another (the camp), where he “loses himself with his people.” His rule is clearly tyrannical, but in a way, it is preferable to the American military occupation, which constantly operates under inconsistent logic (“We are here to lend a helping hand,” one minute, “Bomb it into the stone age, son,” the next). While the camp does not quite “restor[e]… white American domesticity on foreign terrain” (Kaplan, 159), replete with domestic comforts and female subservience, it allows Kurtz to assert paternal dominance in a way that is also colonial. Thus, the camp nuances Kaplan’s argument: it mobilizes a domestic sphere from within a foreign one in a way that also governs native bodies.

However, the men and women who make up the domestic sphere of the camp (most of them non-white) are rendered silent in this sequence. No spoken language or written text attaches cultural signifiers to their bodies, and no movement in the early shots of the sequence give them shape or human qualities. In this way, they become as hollow as the men and women of early ethnographic films, where the “inhabitants of the unindustrialized world were posed for the contemplation of citizens of the modern world” (Gunning, 29). Coppola goes as far as to visualize the ills of empire in Kurtz’s crumbling jungle fortress, without offering an alternative to a history of representations that stretches back to early cinema.

Ultimately, what Coppola (and Kaplan) fail to acknowledge are the ways in which domesticating foreign spaces does not only reveal damning truths about empire, but fails to reveal truths about the people who occupy those spaces. Mute natives exist only to reinforce Kurtz’s rule, reproducing the white man’s colonial fantasy. Otherwise, they are hardly even considered by the film, which centers the narrative on Kurtz and Willard’s fictional confrontation. So focused on revealing the war’s fallacies through melodrama and irony, Coppola forgets about the exact people it tyrannizes, ignoring a crucial dimension of how empire is justified and imagined: through the silencing of native bodies.