The young addict is an enticing archetype in contemporary film. A lighter hovering under a bent spoon, the burbling remedy in its bowl, a band slapping against tortured flesh; the ritual of heroin addiction befits cinematic cliché. Neil Armfield’s Candy adds little to this potentially exhausted narrative, but his aesthetic treatment of downward-spiraling youth is worthy of analysis. With its evocative title and equally redolent composition, Candy offers a perversely childish rendering of temptation and attachment.

Young lovers Dan and Candy (Heath Ledger and Abbie Cornish) descend through three tiers––Heaven, Earth, and Hell––on their pilgrimage toward self-destruction. With these allusive subtitles, Armfield adds a biblical accent to the pedestrian monotony of middle-class addiction. The film’s overly-aesthetic visuals and hyper-romantic themes border on pretension, but equally narcissistic are its characters who take on the chimerical roles of Adam and Eve as they plummet into the depths of depravity and ultimately destroy themselves. Beautiful desire becomes ugly reliance, and Candy entwines infatuation and heroin abuse into an enchanting nightmare.

Heaven. Aspiring poet and budding artist, Dan and Candy drift through a bohemian dreamscape in the throws of opiate-laced lust. Love’s novelty proves muse enough when Candy shows Dan her newest piece called “An Afternoon of Extravagant Delight”; “it’s us,” she whispers just before another sexual spree. Dressed loosely in white linen, an angelic Candy removes Dan’s apple red T-shirt. It is a fleeting scene, but symbolic nonetheless. Perhaps low-hanging fruit, but this playful seduction and figurative loss of innocence fronts a much more harrowing dialogue about temptation.

Extending the metaphor, Armfield constructs a saturnine relationship between addiction and creed when Candy takes her first venous dose in a bathtub. With Dan at her side still dressed in red, the image of a naked, strung-out Candy is Armfield’s morbid quip of a baptism; the beginning of a ritual. Consequently, Candy overdoses and interrupts the serenity, and Dan must coax her back to consciousness. Addiction becomes a sort of religion wherein sex and heroin translate into doctrine, and Armfield composes a liaison between artistic expression, erotic exploration, and drug experimentation in “Heaven” that verges on determinism. He glorifies the fall (the original sin, if you will) to expose the blindness of his characters to their own ruin.

Earth. What was bliss becomes denial in this middle chapter when reality confronts Dan and Candy’s ambivalent self-absorption. Even on the couple’s wedding day, the guests wear black to match the bride, and the marital affair is cloaked in the essence of a funeral. Armfield successfully reverses the narrative of a classic beginning, shadowing the event with a certain foreboding that indicates the devastating years to come. Candy turns to her new profession as a prostitute, supporting the addiction of both herself and her husband.

Art and creation are distant from these scenes, and aesthetically composed images of romance and youthfulness fade comparably. Meaning can no longer be gleaned from the flowing linen or poignantly colored shirts, and Armfield trades the previously-symbolic garments of his characters for monochrome athleisure clothing. The religious imagery endures, except masses are now led by Dan’s adoptive father figure who indulges the young couple’s heroin communion around a dining room table. Candy and Dan sink deeper into the greys, blacks, and navy blues of their surroundings. Life is no longer a bohemian reverie, but a realistic appraisal of the middle-class junkie.

Hell. In the wake of contemporary drug-enthused cinema, like Requiem for a Dream and Trainspotting, critics claim that the effectiveness of any drug movie can be measured by the strength of its detox. Candy certainly doesn’t sweeten cold-turkey when the young couple decides to quit “the right way this time” with the news of Candy’s pregnancy. Amid a neo-psychedelic pop soundtrack and dim lighting, the two battle against withdrawal. Live evangelical masses blare from the TV. A white camisole sticks to Candy’s derelict pregnant figure, and with the religious imagery that saturates the film, the viewer cannot help but gaze upon a ruined virgin Mary.

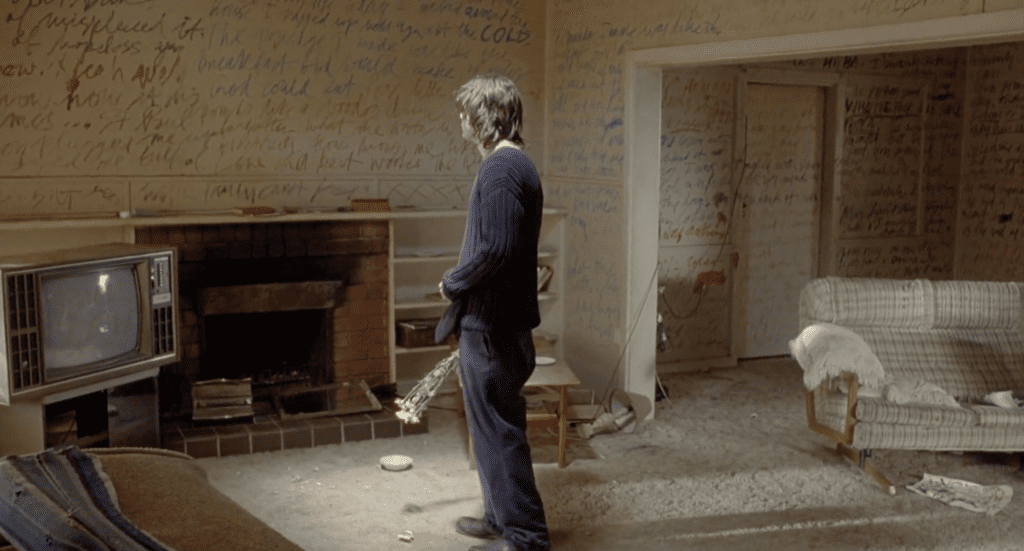

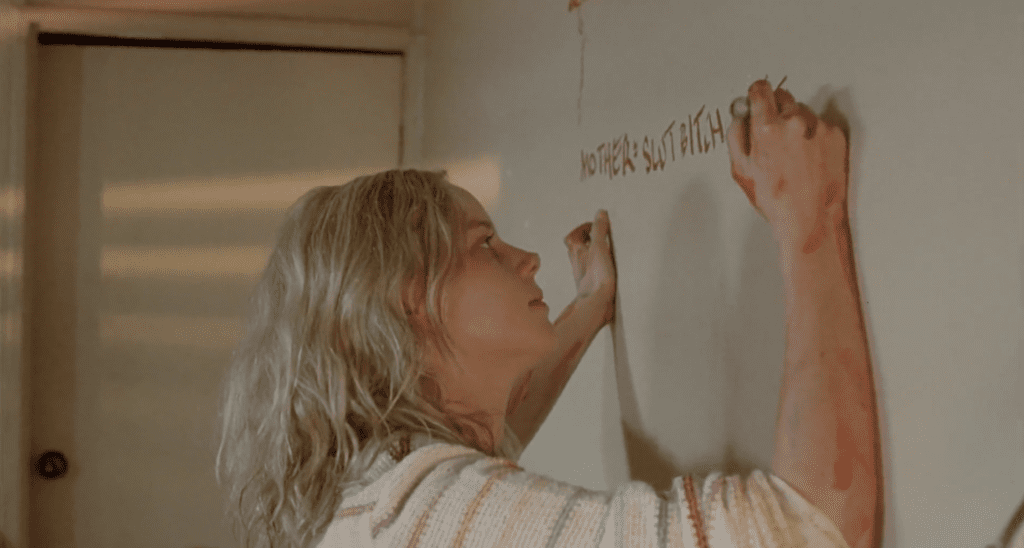

The film culminates in a climactic bought of artistic expression when Candy experiences a psychotic break. She writes a long poem in frantic prose on the walls of their house beginning with, “Once upon a time there was Candy and Dan.” The poem is harrowing, tangling elements of fairytale into the spiraling story of the couple’s addiction; art does, indeed, seem to imitate life. Dan wakes up to Candy’s masterpiece and his monochrome navy figure is isolated against the bright words that adorn the patina walls. The scene is shot almost too beautifully, and Armfield’s deterministic lens exposes the fallacy of aesthetics; art, creation, and romance mock Dan’s life as nothing but a false Eden.

" alt="">

" alt="">