Directed by Wong Kar-Wai — an atypical auteur of Second Wave Hong Kong cinema —and released at the dawn of the new millennium, “In the Mood for Love” captures love and longing against the exquisite backdrop of an evolving Hong Kong.

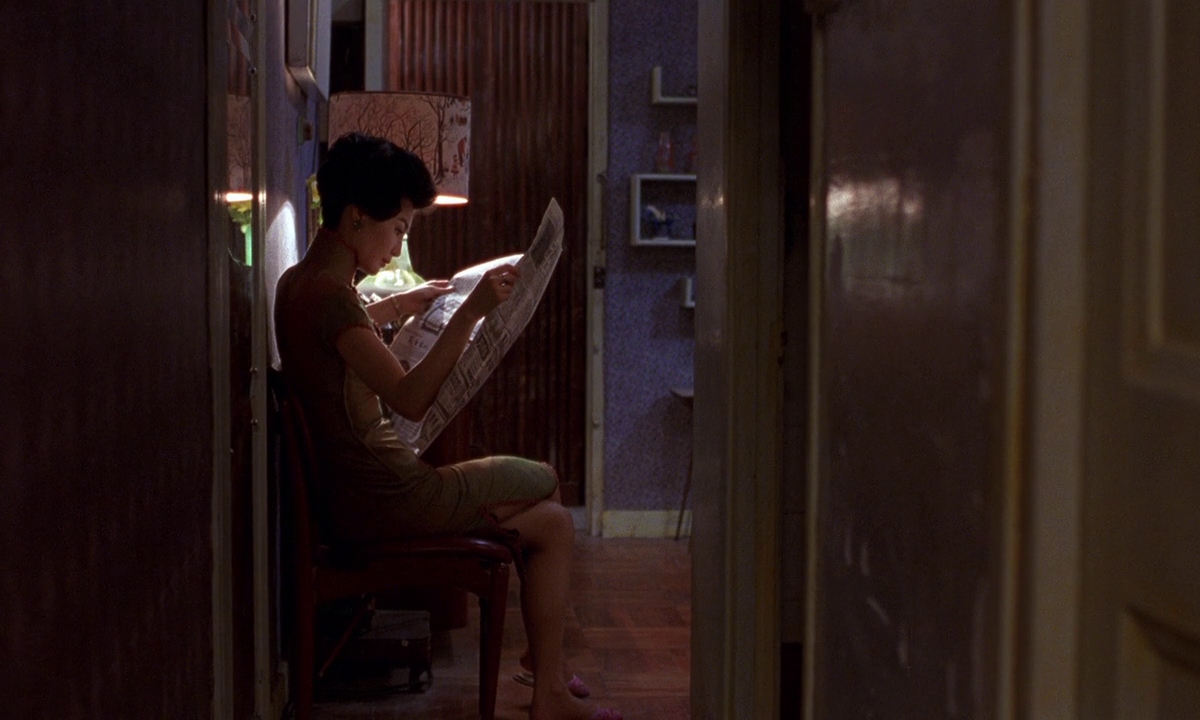

A story of impossible love, loneliness, and common suffering, the film follows Chow (Tony Leng) and Ms. Chan (Maggie Cheung) as they form a decades-long bond that is ultimately destined for failure. Imprisoned by the conventions and morals of their time, as well as the mutual pain of betrayal, Kar-Wai’s protagonists are achingly inhibited as they strive to maintain the appearance of indifference while wracked by overpowering emotions that can never be spoken.

As the film progresses and the years tick by, it becomes clear that time is the centerpiece of “In the Mood for Love,” both as a testament to Hong Kong’s colonialist past and in its portrayal of memory. The film is set in a precise historical moment, capturing the progressive westernization of Hong Kong during the 1960s. This historical change influences the dynamics of the couple, contributing to their sense of loss and up-rootedness, as well as their search for a place in the world where their love has the right to exist. Despite their love being impossible, the director manages to carve out a metaphysical space for it, guaranteeing the two lovers a respite within the ethereal dimension of memory.

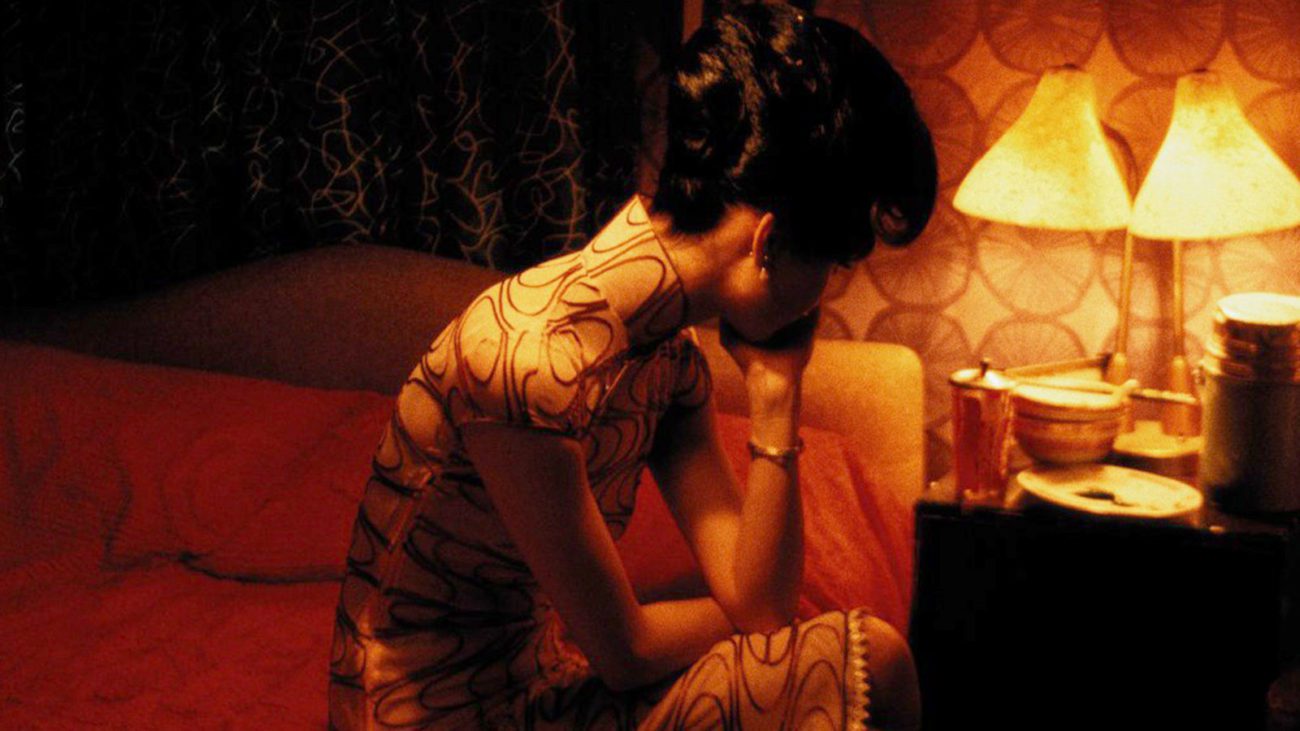

Through soft tracking and use of slow motion, Chow and Ms. Chan’s relationship is sealed in the unsaid. In the film’s effort to understand and render invisible feelings, the art of omission dominates. It is not by chance the director declares that he eliminated many scenes in editing to “preserve the essential.” Throughout his film, Kar-Wai embraces the poetics and elegance of restraint, and this ethos is reflected in every detail. The camera caresses Kar-Wai’s characters, following them throughout the years, without ever truly revealing their interiority. Only Ms. Chan’s “cheongsams” demarcate the passage of time. The “cheongsam” is a traditional female Manchu dress: the last Chinese dynasty that fell in 1912. Ms. Chan’s garb is an extension of herself and the image she wants to offer to the world — if only to go to buy some rice. An antidote to solitude? A device to forget about her existence? Both? The colors Ms. Chan wears interrupt the gray monotony of her everyday life. Her manner of dress is not only a way to show off her beauty, but also her last form of attachment to the romance of the past.

Unable to reconcile the tension between past and present, fantasy and reality, private desire and the public obligation, the protagonists appear to fracture; Kar-Wai’s use of shadow denotes an external and internal shattering. To deliver this love untouched by time, the characters must inhabit an aching memory. Fittingly, the film closes in the dreamy, foreign ruins of Angkor Wat. Separated from Ms. Chan by time and thousands of miles, Chow finally speaks his love into an abandoned crag where his secret, so sweet and pure, can live forever.

" alt="">

" alt="">