Born in Iowa in 1938, Jean Seberg is remembered today as an icon and muse of the Nouvelle Vague, famed for audacious and alluring performances in films like Jean-luc Godard’s Breathless and Philippe Garrel’s experimental work Les Hautes Solitudes. (She was even an early favorite for the role of Julie in Truffaut’s Day for Night — a partnership, which unfortunately never came to fruition.) But behind her quintessential short hair and doe-eyed countenance hides a much more complex story. Jean Seberg is not merely a symbol of spritely exoticism. Her story is a testament to the manipulative and destructive power of media narrative.

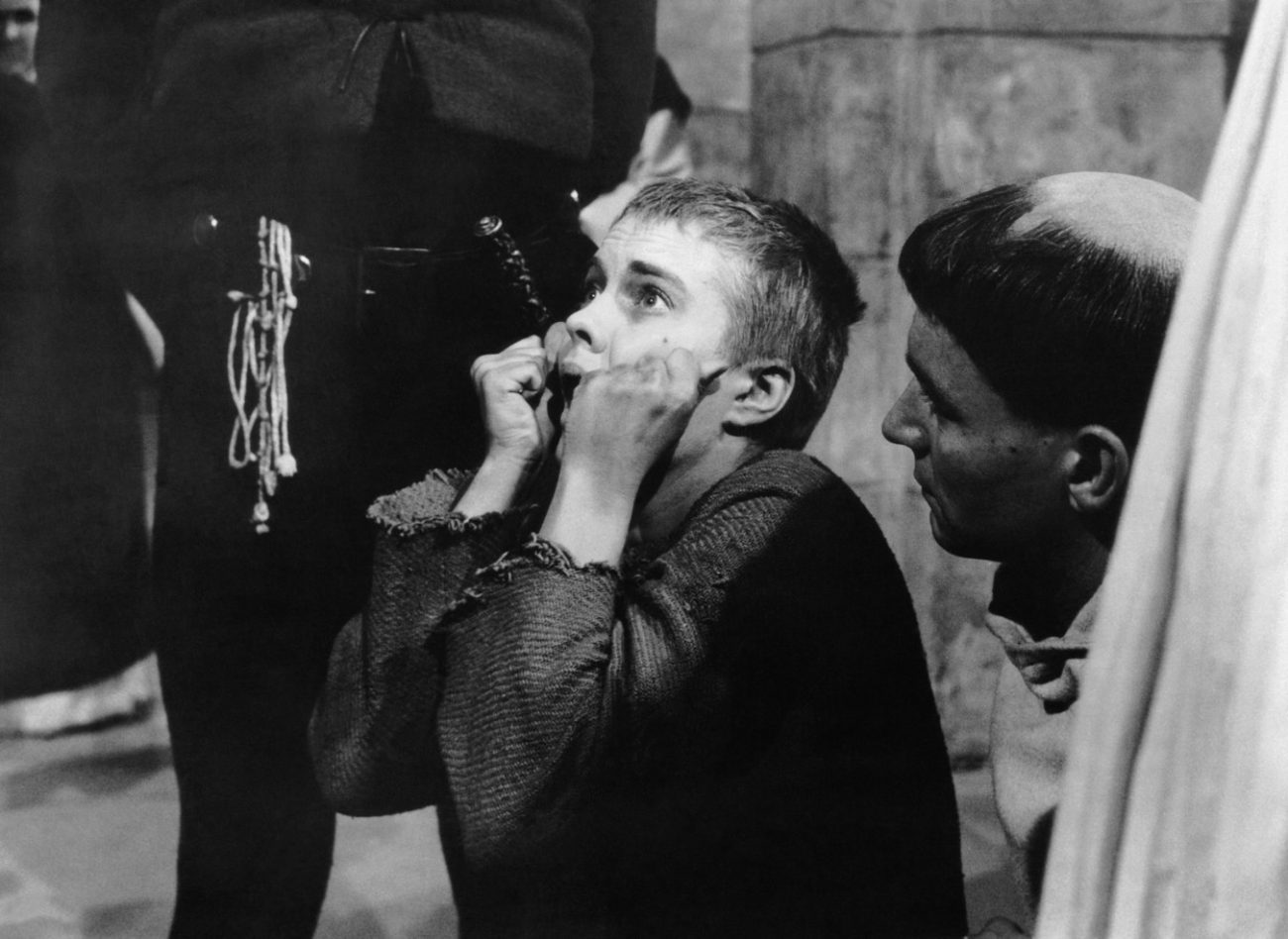

As a young woman, Jean was discovered by Otto Preminger (selected from among 1,800 young novices in a competition), debuting in his 1957 film Saint Joan — an adaptation of the story of Joan of Arc. Though not a commercial success, Jean Seberg’s performance as the strong-willed saint immediately captured audiences. Her cropped, garçonne hair and her mischievous air conveyed a modern, winking form of femininity that set her apart from other young starlets at that time.

In later roles, like Cecilia in Bonjour Tristesse (1958), Seberg continued to shine and even enacted her payback for Saint Joan’s commercial failure. Watching Bonjour Tristesse, one cannot help but notice that Seberg’s Cecilia is credibly and delightfully out of line — a capricious, selfish, and spiteful girl without redemption. So it is unsurprising that when the film achieved international success Seberg found herself at the center — her unusual lolita aesthetic attracting French audiences in droves. This was naturally where she would go next.

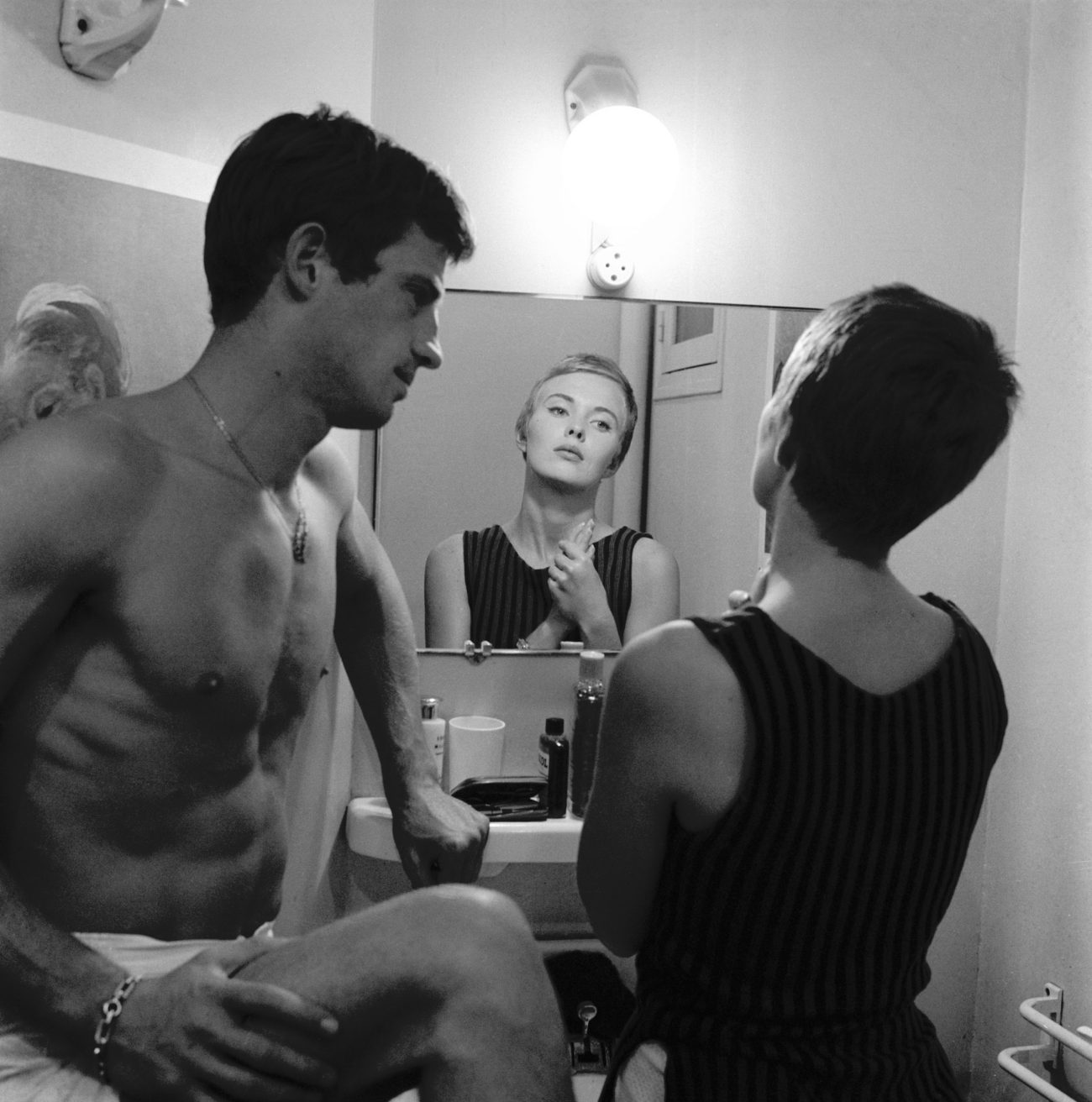

1959 was a year of consecration for Seberg. It was the year she filmed Breathless, directed by Jean-Luc Godard, a pioneer of modern cinema. At the time, Godard and several other French auteurs were interested in an entirely new way of making films. Together they shaped a new movement, a creative under-current that would be called “Nouvelle Vague.” Inspired by Italian Neorealism, and American B-series films, Godard strived for authenticity in cinema, privileging the exaltation of reality above all else. Godard’s films sought to stage and (in a way) serve as a faithful reflection of reality. And so Seberg’s inexperience proved an allure for the director. He chose her for the role of Patricia, a young American student struggling with the outlaw Belmondo, and confirmed her as an absolute authority on the character. Seberg’s performances in iconic scenes throughout Breathless, like the walk on the Champs-Elysées, are crystallized so deeply in the collective imagination, that, in 1990, the photographer Ellen von Unwerth paid tribute to the character in Vogue France.

The years following Breathless were years of intense work for Seberg, who performed in several films including Lilith (1964) by Robert Rossen and Moment to Moment (1966) by Mervin LeRoy. During her time in France, the actress met and married the famous writer Roman Kacev, naturalized French with the name of Romain Gary (it is possible to recognize Seberg’s portrait in his novel Talent Scout). The two had a deep bond on an intellectual level, sharing the same political ideals and committing themselves to the same causes and charities. These were the years of the Cold War — years that were at once formative and tense. Civil liberty was (rightly) on the agenda, and political movements, including the Black Panthers, rose to represent the rights of minorities.

Seberg, having little in common with the superficial frivolousness of her first movie characters, supported the Black Panther organization with several donations. Unfortunately, this led to her inclusion in the “COINTELPRO” program — an FBI surveillance and counterintelligence program meant to discredit personalities considered “uncomfortable” to the American political regime. Their veritable campaign of defamation would be the source of future mental crises for Seberg and shape her world view for the rest of her life. Branded as a black sheep, Jean Seberg was blacklisted — ousted from every production company. And, in 1970, Newsweek published a piece asserting Jean Seberg’s connection with Raymond Hewitt, one of the leaders of the Black Panthers. The article even implied that she was pregnant by him. The combined shock and psychological trauma of these events caused Seberg to spiral into depression, which lasted for years, ultimately culminating in her suicide.

The story of Jean Seberg is full of contradictions and contrasts, where the image proposed by the media almost never matches reality. According to Roland Barthes, media is a truth simulator — a simulator that is nonetheless capable of transforming a person’s life. “The photograph is literally an emanation of the referent,” Barthes writes. “From a real body, which was there, proceed radiations which ultimately touch me, who am here; the duration of the transmission is insignificant; the photograph of the missing being, as Sontag says, will touch me like the delayed rays of a star” (Roland Barthes, Camera Lucidia). If the news media is a truth simulator, then Hollywood (with its endless imagery) is a myth generator. So when Jean Seberg was classified as a public enemy in 1970, this was simply accepted as the new, natural order of things

In 1979, Jean Seberg’s dead body was found inside of a Renault along with her last written message: “Forgive me. I can no longer live with my nerves.” That same year, the Federal Bureau of Investigation acknowledged that its agents had plotted to smear the actress’s reputation by planting the Newsweek story. In retrospect, we cast Jean Seberg’s life within a three-act structure, but her story is so much more complex than that. It is a testament to the dark outcomes that can occur when truth and myth intermingle

" alt="">

" alt="">