“Look at what I bought, not a second thought, oh, Romeo”

– “Lolita”, Lana Del Rey

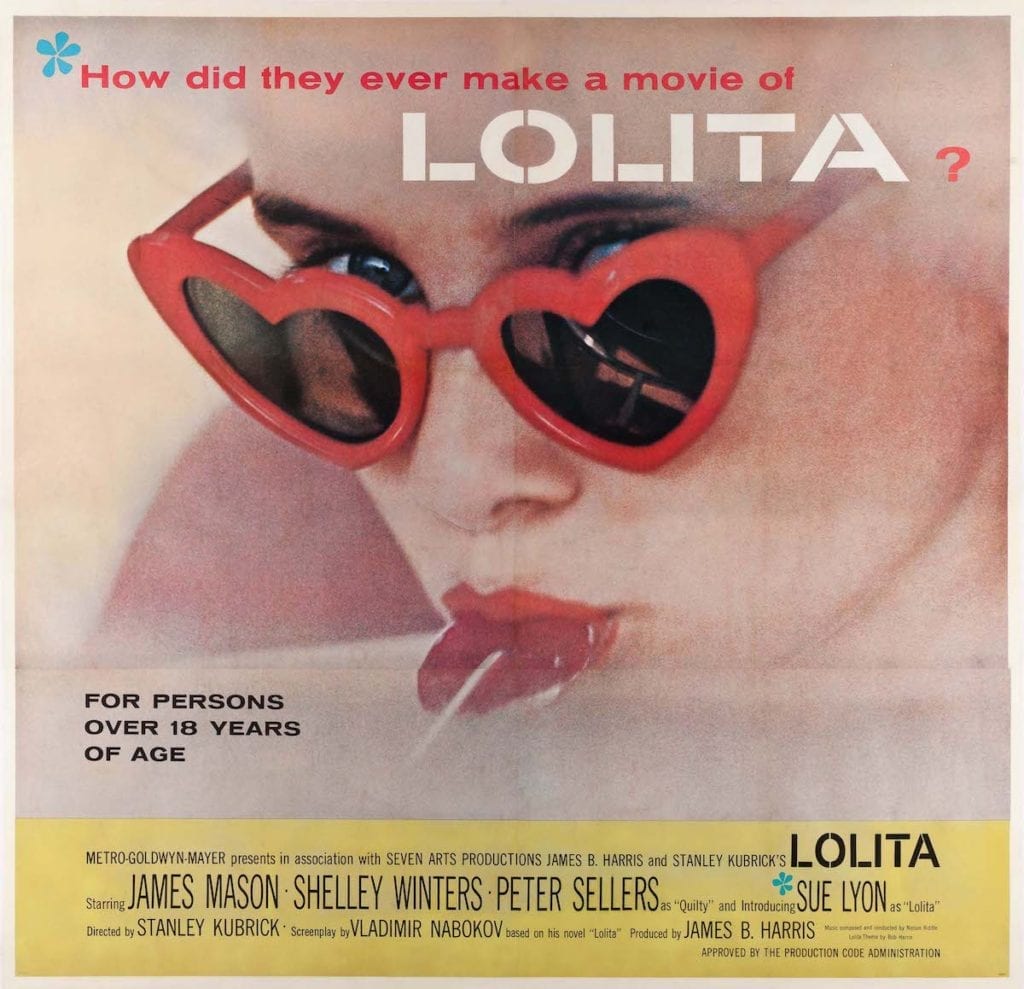

In the first season of the popular teen melodrama Riverdale (2017) a character named Miss Grundy dons a pair of cherry red, heart-shaped sunglasses as she leers at two teenage boys. The moment is played as high camp, and the audience implicitly understands the sexual nature of Miss Grundy’s gaze, the inappropriateness of her desire, through the sign of her eyewear. Her youthful sunglasses are, of course, a nod to Lolita’s shades in Stanley Kubrick’s emotionally-faithful 1962 filmic adaptation of the Vladimir Nabokov novel. Sunglasses so intimately intertwined with the American myth of girlhood that their presence in the scene functions as shorthand for desire and disaster, erotic power not yet controlled.

The story of Lolita is commonly evoked in archetypal, piecemeal fashion. To invoke Lolita is to invoke cultural conversations surrounding sexual politics (i.e., young Dolores “Lolita” Haze is the victim of erstwhile academic Humbert Humbert’s pedophilic lust). While this aspect is undoubtedly true — that harm is committed against Lolita’s person — the dominance of this point in cultural criticism displays a lack of interest in Lolita’s potential subjecthood and agency.

The audience is purposefully aligned with Humbert’s point of view for nearly all of Kubrick’s film. It is the same in Nabokov’s novel. There is very little exteriority, and, as such, we only see Lolita as Humbert sees her. From the outside. But if we pay close attention to Lolita’s styling, the accessories and childhood trinkets to which she has access, we might begin to imagine her inner world.

In the film’s first act the viewer is introduced to Lolita’s mother, Charlotte Haze (played by Shelley Winters), as she gives Humbert (James Mason) a tour of her home. Charlotte, with a mix of financial and sexual desperation, fervently hopes for Humbert to become her tenant while he works on his academic manuscript over the summer. It is during Charlotte’s tour of the house that Humbert spies Lolita (Sue Lyon) sunbathing in her backyard. He stares at the girl, the crooning music from her radio washing over her mother’s words, as he enthusiastically agrees to stay. At this point in the novel Humbert remarks on Lolita’s uncanny resemblance to a haunting childhood romance, “there was my Riviera love peering at me over dark glasses.”[1] Kubrick in turn plays with space, sound, and costuming to emphasize the importance of the encounter: Lolita’s presence dominates Humbert’s gaze, she takes up space, and, through her sunglasses looks right back at him.

The site of Lolita and Humbert’s first encounter, their joint discovery of one another, is a critical moment because it also reaffirms the viewer’s uneasy alignment with Humbert’s point of view. Like Humbert, we replace Lolita’s inaccessible parts with stories; stories about what kind of girl she is, her boldness, and her frankness, until there are enough words to satisfy the empty spaces. Even now when we conjure the image of Sue Lyon’s shaded eyes, we think of two perfectly symmetrical heart shaped veils. However, Lolita never wore heart shaped sunglasses in Kubrick’s film. These sunglasses, so fixed within cultural memory, only appear in the film’s publicity photos and the soundtrack’s album cover.

This revelation requires a shift in inquiry. The real question is not what can be gleamed about a girl from her things, but rather what does it mean for a girl’s things to define her and her memory? What does it mean for a pair of sunglasses to form an idea of girlhood, to make girlhood accessible through purchase? Lolita is thus the story of girlhood and its mass-produced fetishization. Lolita is not only Humbert’s object of illicit desire but an every-girl occupying the liminal space between being wanted and wanting; her things both provide and attract power; a pair of sunglasses transfigure her from girl into myth.

Nabokov considered his work to be a parody of Freudian thought, a stance which Kubrick flirts with throughout the film. Nabokov even went on record with his low opinion of Freud’s theories, stating, “Freudism and all it has tainted with its grotesque implications and methods appears to me to be one of the vilest deceits practiced by people on themselves and on others.”[2] Yet parody is a complex act that necessitates a conscious decision to imitate. It bears a passing resemblance to a Freudian slip: what comes out in the excesses of parody is important and bears weight.

The film’s emphasis on Lolita’s costuming, specifically her sunglasses, informs the cultural fascination. Moreover, the sunglasses themselves (both the Riviera cat-eyes and the hearts) function under the Freudian sign of the fetish. Within a capitalist context, the fetish — an “inanimate object which bears an assignable relation to the person whom it replaces and preferably to that person’s sexuality” [3] — occupies an amplified level of significance as it is the dominant language of desire. Two scenes within the film lay bare Kubrick’s discourse of objects: how this discourse winds throughout the narrative, the consequences of these relationships for Lolita, and our collective idea of Lolita.

About midway through the film, Humbert picks Lolita up from summer camp and they are on the road traveling together as incestuous stepfather and daughter. Lolita believes they are headed to visit her mother in the hospital but unbeknownst to her, her mother has already died. Prior to Humbert taking her from camp, he passively triggered a series of events which caused her mother to be hit by a car. They are outside of Lepingville, Ohio when Humbert, tired of Lolita’s questions, tells her the truth about her mother. The next scene opens in the bedroom of a non-descript hotel room. Lolita enters the frame and Humbert cradles her head in his lap. She begins to lament her uncertain future, “what about all my things back in Ramsdale, at the house?” Humbert comforts her with the promise, “we’ll take care of those things . . .I can buy you new ones, I’ll buy you the best.” Lolita’s belongings are intertwined with her grief, her selfhood, her future.

The second scene shapes the conditions of the film’s climax. Humbert and Lolita have left the town of Beardsley, Ohio where they settled for a time as “father and daughter.” As Lolita begins to rebel and lie and spend more time with the mysterious playwright Clare Quilty (Peter Sellers) Humbert grows increasingly paranoid. Humbert, convinced that he and Lolita are being surveilled (strange coincidences that are, in truth, the joint machinations of Quilty and Lolita), absconds with Lolita on a wandering, cross-country road trip. While on the road, Lolita falls ill and must be hospitalized. Humbert visits her hospital room several days after he checks her in. Lolita sits in bed reading a magazine; a nurse leaves the room upon Humbert’s arrival. Dark glasses rest folded near Lolita’s breakfast tray. Humbert picks up the glasses, anxiously fiddles with them and exclaims, “are these yours . . . since when have nurses worn dark glasses when on duty?!” He tries on the glasses with an itching distress, roughly takes them off, then puts them back on. He takes off the sunglasses one last time to ask Lolita, “when can you leave?” Lolita evades his increasingly frantic questions and goodbye kiss. Both Humbert and Lolita avoid touching the glasses. When Humbert returns to the hospital Lolita is gone. They do not see each again for years.

While neither Lolita’s hotel grief nor Humbert’s hospital unraveling provide definitive answers on the collective importance of the heart-shaped glasses, both scenes interrogate the conditions of collapse in the face of the fetish. When Lolita and Humbert are confronted by objects that do not act as they should, do not occupy their appropriate spaces, they suffer, their self-hood is undone.

Lolita’s story of ill-fated passion is inextricable from the tale of a man undone by fantasy. The film closes as it opens, with Humbert entering a seemingly-abandoned estate, its rooms littered with bourgeoise tchotchkes, empty booze bottles, and cigarette butts. Claire Quilty, silk-clad libertine, playwright, and Humbert’s hungry dark shadow, appears from under a bedsheet covered armchair. The standoff between these two men amidst the debauched rubble of Quilty’s aristocratic role play exposes them — not only as doppelgängers but as charlatans, lords of no manor. Though both Humbert and Quilty are predators, they fall prey to the almighty commodity. Taken with an idea(l) of innocence, youth, and girlhood behind dark glasses. Available and corruptible, for the right price. As Humbert chases Quilty through his house he shoots and hits a painting of a young woman. The bullet rips through her pale cheek and destroys the painting’s illusion of impenetrable perfection.

Kubrick means for the audience to feel that Lolita’s fate is akin to Quilty’s bullet riddled painting; this equivalency is made so that we understand the violence of Humbert’s actions upon Lolita’s life. However, these interpretations of the painting tend to veer towards the proscriptive as Lolita the person is both more and less than Lolita the fantasy. When these moments of rupture occur (objects again not behaving as they should) viewers gain something akin to knowledge of Lolita. Though this understanding is perhaps superficial, the very contours of the discourse render it the only available form of knowledge. Near the film’s end an older Lolita tells Humbert, and by extension the viewer, “my world didn’t revolve around you.” This is both a realization and indictment that Lolita was not the only one wearing heart shaped glasses. Under a system where objects become shorthand for innocence and experience, erotic power desired and disavowed, we’re all possessors and the possessed.

Works Cited

" alt="">

" alt="">