Stanley Kubrick once said that “the screen is a magic medium. It has such power that it can retain interest as it conveys emotions and mood that no other art form can hope to tackle.” This belief is demonstrated throughout his cinematic works. But it is particularly apparent in the 1971 cult classic A Clockwork Orange, a film that places among the most political and iconic art forms in cinematic history.

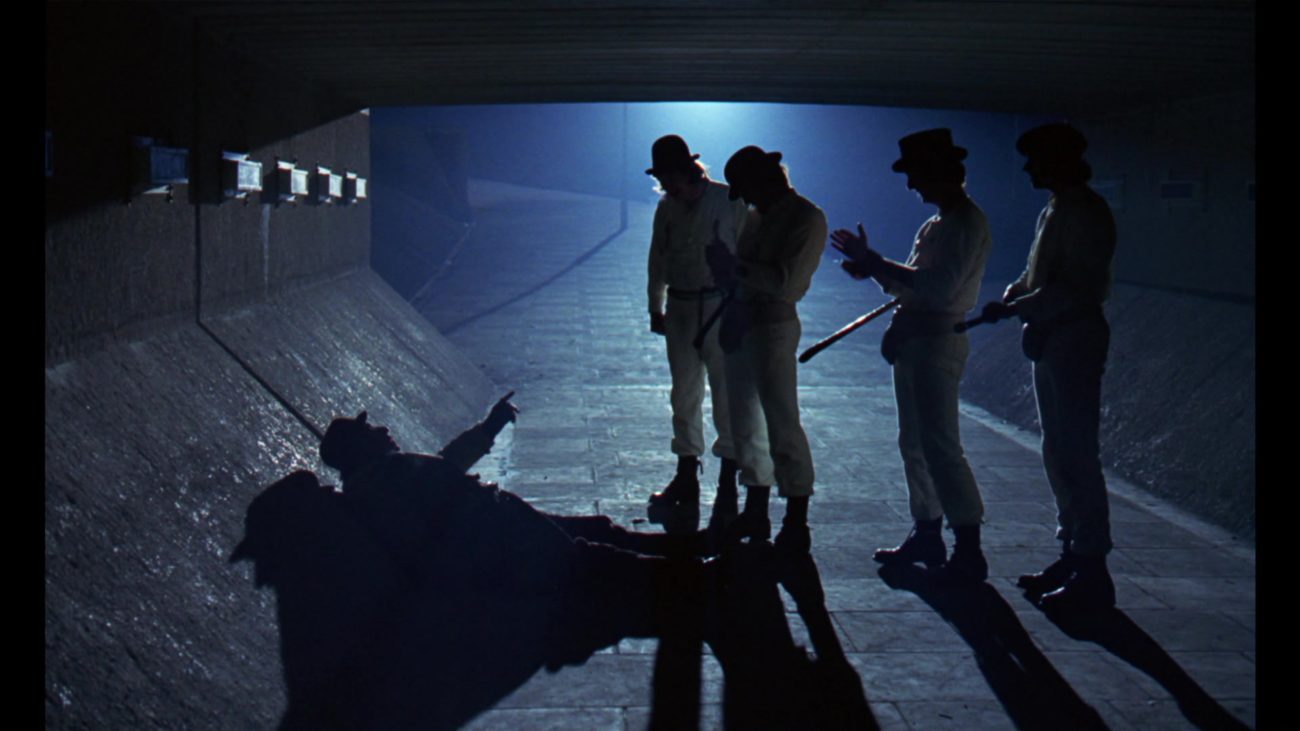

Based on Anthony Burgess’s 1962 novel of the same name, the film follows Alex, played by Malcolm McDowell, and his rebellious, sadistic gang of ‘Droogs’ who live in a futuristic London and spend their nights committing a multitude of violent crimes for their own entertainment. After committing murder (and finally getting caught), Alex is sent to prison where he naively agrees to undertake ‘Ludovico therapy,’ an attempt to rid him of his sadistic desires through controlled exposure to visual and auditory stimuli. Whether he is ‘cured,’ however, is questionable.

Created by the award-winning French costume designer Milena Canonero, the film’s crisp costume designs stand in stark contrast with its Brutalist backdrop. Canonero worked closely with Kubrick, to construct colors and patterns that would reflect the character’s demeanors, which ultimately circulate around violence.

Influenced by the Mod movement of the 1960s (itself, a reaction to post-war, free love sentiments), the ‘Droogs’ iconic costume designs – made up of white jumpsuits, suspenders and working man boots – pay homage to fascist subculture while their black bowler hats and canes mockingly gesture toward attire worn by gentlemen types in London.

The eyeballs Canonero attached to Alex’s cuffs suggest that he idolizes himself as the eye of the law and the primary overseer of his gang’s ultra-violent activities. In one iconic scene at the Korova Milk Bar (an objectifying space in every aspect), their feet rest on the female sculptures as furniture, indicating the gang’s total disregard for the opposite sex, a theme that carries throughout the film.

One of Clockwork’s most distinctive features is its portrayal of ultra-violence as libidinal drive within Modernism, a perversion of the swinging 60s. In the opening scenes, viewers are forced to watch a disturbing sequence of attempted rape in a theatre – positioning women, from the start, as objects of systemic scopic and physical violence to be consumed. The victim’s harrowing cries echo throughout the space accompanied by buoyant orchestral music. A montage of camera angles follows her naked body left and right as she’s pulled to and fro like a rag doll. This distinct style forces an uncomfortable association between the generic trappings of comedy and the very real horrors of gang rape. In fact, Kubrick’s unflinching portrayals of violence, robbery, and murder led to this film being banned from the UK due to fears that these acts would be copied.

Kubrick’s trademark use of color and pattern, have been exhaustively discussed within the context of his filmography: ‘The Shining,’ ‘2001: A Space Odyssey,’ and more. And these elements are no less crucial to A Clockwork Orange, especially when it comes to the famous break-in scenes.

In the most famous of these, Alex’s victim wears a tight red jumpsuit (symbolic of love and lust but also danger and violence), indicating the gang’s intentions of sexual violence. Posed in a mirrored hallway, her reflection is visible on either side of the frame, offering the viewer three different angles of her body. Through this intentional configuration, Kubrick intentionally positions the victim as an object of the male gaze. The checkered chess floor implies that Alex perceives his violence and behavior towards women as nothing more than a sadistic game whereby he is the only winner.

The Droogs (naturally) break-in, and a chaotic montage of long shots captures the gang as they ransack the home, completely dominating the frame. Thrown over one of the Droog’s shoulders like an animal, the woman in red is flung around in circles. The footage whirls with increasing levels of visual energy, conveying her emotions of panic as well as the gang’s crazed mindset.

Alex sings the line ‘ready for love,’ as he cuts apart her clothing — the horrible implication being that love and rape are the same. An uncomfortable close-up lingers upon her terrified tape-covered expression as she moans and shrieks. With no-where else in the frame for the eye to look, it is apparent where Kubrick wants our attention. The scene drives to an end with a low-angle center-dominant shot of Alex staring right at the viewer.

In the second break-in, Kubrick again manipulates his frames to portray women as objects of systemic violence and men acting as dominators. Here, a woman performs yoga in her home. She raises herself onto her shoulders and lets her legs cascade down towards the camera.

But her demeanor and dress stand in stark contrast to the lady in red. The color of her leotard (green) symbolizes the natural world as well as money and ambition. Her decorating aesthetic points to this interpretation as well. Her apartment is peppered with artworks depicting open male and female sexuality. Most notably, a large sculpture of a phallus by Herman Makkink. These artworks become particularly interesting as she proceeds to defend herself against the murderous Alex.

A shaky handheld camera works around the two as they appear to frolic in time with the music, a frantic orchestral symphony. The jittery camera work replicates the first scene, but this break-in plays out quite differently. In a humorously literal moment, Alex brings Makkink’s penis sculpture right down over the poor woman’s head, smashing “nature” and “free love” and “female ambition” into what I can only assume are a hundred bloody shards. In a grotesque show of visual brilliance, Kubrick pans the camera in on a close-up of her wide-open mouth before abruptly cutting to black at the moment of her death, further emphasizing the idea of sexuality and violence (and death) as innately tied within the new world order.

Clockwork spends an extensive amount of time portraying female victimization (in addition to violence of all kinds), but even Alex is not immune. While incarcerated, he agrees to undergo the unorthodox ‘Ludovico Treatment’ in return for a shorter sentence. At the hands of the state, he is forced to partake in this highly controversial, stimulus conditioning therapy to “cure” his illness of ultra-violence. And it soon becomes clear that the state’s methods are a far cry from the tender care that one might expect at the hands of health professionals. In fact, it is yet another violation — another form of rape even. Alex, once committed, is brainwashed, dehumanized, and exposed to an agonizing and inhumane form of aversion therapy. It’s checkmate for Alex as he finds himself the main player in a very different game. One that can only truly benefit the government as a method of castrating control.

In one scene, a close-up captures Alex’s alarming facial expression as his eyes are forced open with metal clamps. The image is emotionally distressing for the viewer, its own form of body horror. Alex cries out and he is scarcely able to move in his straightjacket, “a horror show co-operative malchick, in the chair of torture.” He is drugged up and forced, again and again, to watch violent sequences whilst suffering from severe induced nausea. Through this cruel form of exposure therapy, the government doctors systemically and unilaterally strip Alex of his core drives, whether they be sexual, violent, or even artistic. (He is no longer able to enjoy the only thing he ever loved in this world, Beethoven.)

Harkening back to the film’s initial scenes, while undergoing treatment and finally being tested to see if he is ‘cured,’ Alex is filmed within theatrical settings: a cinema and a theatre stage. In this sense, the violent logic of A Clockwork Orange is reversed. The witnessed object — the cinematic object to be consumed — is no longer an object of violence. Rather, it is the viewer. Alex is brought to an auditorium to display his “progress.” His handlers introduce a semi-naked woman. She wears a crown of light, signifying that she, in comparison with Alex at this moment, is powerful. A low-angle shot reaffirms her authority as she towers over him like a goddess, and he looks up to her with sheer desperation in his eyes. Yet, he cannot touch her. Instead he wretches with sickness induced by his conditioning. Unlike the ladies in red and green, Kubrick places her as the final, naked dominant female figure over the male.

Released in the wake of second-wave feminism, A Clockwork Orange brings issues of domesticity, sexuality, rape, and reproduction within a post-industrial world to life through attentive cinematography and intricate camera angles. Characters, costumes, color, and iconography are bound together to communicate specific messages about women and their complex configuration within the social fabric of the time. But it is also an interesting reflection on the modern states’ monopoly on violence and the ways in which this violence is systemically enacted upon the individual and his (as well as her) dignity. In fact, in one of the film’s later scenes, Alex is surprised to discover that his former Droogs have become police officers who then beat him mercilessly.

In collaboration with Canonero’s intricate costume designs, Kubrick’s message continues to resonate to this day. Where A Clockwork Orange particularly succeeds is in its manic portrayal of violence, and horror and humor in equal doses — much like reality, the film is a mixture of all three. As Alex says at one point in the film, “It’s funny how the colors of the real world only seem real when you viddy them on the screen.”

" alt="">

" alt="">