“It doesn’t seem inaccurate to say most people in this society who aren’t actively mad are, at best, reformed or potential lunatics”

Susan Sontag, The Pornographic Imagination

“You are supposed to know it, but it’s prohibited to publicly state it. This is the mystery of customs and its crucial for our social co-existence and it’s here that ideology inscribes itself…Prohibition is prohibited to be stated publicly”

Slavoj Zizek

When I first discovered Dir. Steve McQueen’s Shame (2011) I was in the middle of the unfolding disaster that was my early twenties. At a time when everything felt out of control, Shame spoke to me on a level I didn’t yet have the maturity to put into words.

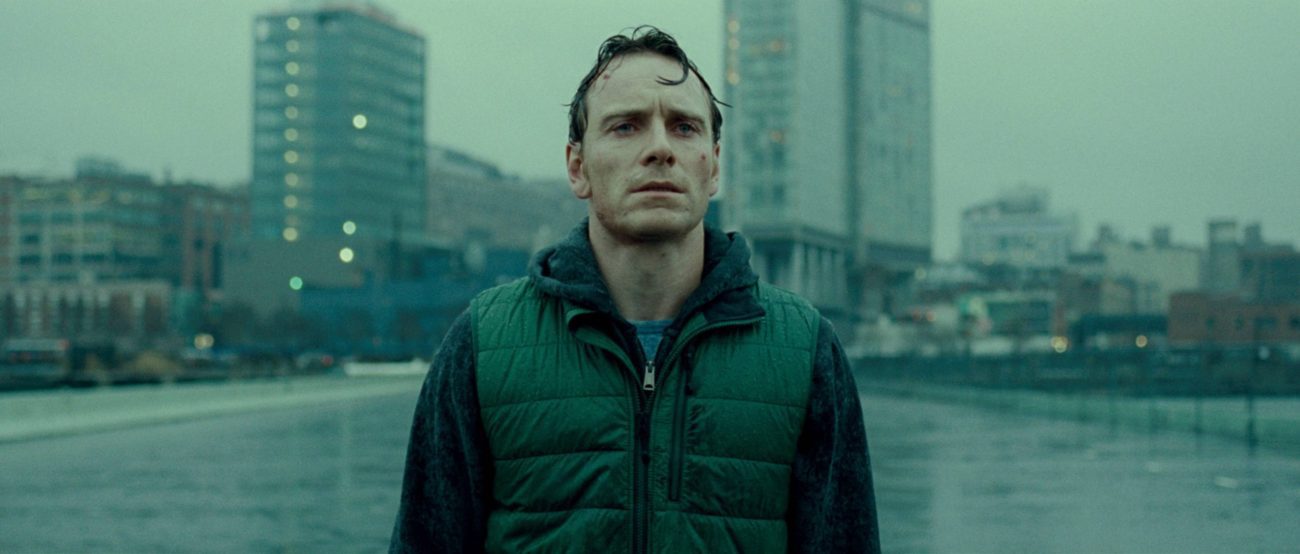

Nearly 10 years older, wiser, and more sober, I returned to McQueen’s treatise on sex addiction only to find that the impact remains largely unchanged. My heart still breaks in the same old places every time I watch Shame‘s patently unlikeable protagonist, Brandon, played by Michael Fassbender, struggle to connect. With his lovers. His surroundings. His family. Strangers. Even the viewers. No matter what he does or how hard he tries. It turns out Shame’s appeal has very little to do with a certain level of maturity, sobriety, or “good-ness” (or insufficiency in these areas). Its meaning is incisive, if not humiliatingly empathetic, no matter where you are in life.

In Shame, Brandon is a sex addict. That much is clear. Every scene is an exercise in either sadness or cringe as he compulsively cruises for one-night-stands, frequents prostitutes, and downloads what I imagine to be potential terabytes of pornography. And then he goes to work. Or back to his apartment where he lives, alone. And then, he jerks off. Because he has to.

The temporal quality of McQueen films feels like reality. In McQueen films, as in life, we are denied the reprieve of a cutaway. It is a masochistic cinematic experience that leaves both actor and viewer naked to the unfolding and often unbearable drama. Another film starring Fassbender, Hunger, documents the last days of Bobby Sands. Here, almost in anticipation of Shame, McQueen deploys the cruelty of realism as he depicts a man slowly starving to death. The film is a beautiful horror as the protagonist withers away in cool, collected sequence. In 12 Years a Slave, McQueen applies this same plain-spoken gaze to slavery in the Antebellum South. The camera conveys moments of torture, of pain, with the cold remove of machinery, as if to say ‘watch this.’

There is no eroticism in Shame. Quite the opposite. What is remarkable about Brandon’s pursuit of the sexual encounter is not its explicitness or frequency. It’s the boredom. Much like the heightened yet subtle sense of dread in Hunger, or even 12 Years a Slave, it is the painfully ordinary, intentional, and transactional quality of these meetings and the extent to which this quality governs every aspect of his existence that make Brandon a truly empathetic (and frightening) character.

Susan Sontag writes that “pornography…points to…the traumatic failure of modern capitalist society to provide authentic outlets… to satisfy the appetite for exalted self-transcending modes of concentration and seriousness.” She goes on to note that “the need of human beings to transcend ‘the personal’ is no less profound than the need to be a person, an individual.” (Sontag 231)

When Brandon goes to the office, he enters the cold, economical world of business. A shiny, glass building filled with handsome men in suits who look very busy and important. We don’t know what his job is, and we never find out. Because it doesn’t really matter. In a film with very little dialogue, as in capitalism, appearances are what count. And what we see is a multimillion-dollar office overlooking one of the world’s most expensive real estate markets. Brandon has the suits, the apartment, the looks, and the mannerisms. What else could possibly matter? There is no third-person omniscient, no narrator, and no sense of psychic interiority. We are provided very little information about Brandon’s history, his feelings, or his anxieties. Instead, we are offered only McQueen’s prolonged, and explicitly voyeuristic look, which is at once profoundly intimate and profoundly superficial in the case of Shame. We are left to construct a narrative from a scattering of visual cues and fragments of dialogue. A gaze that is consciously surface-level and lensed. Brandon is cast against a reflective, modernist backdrop, usually on the other side of an impenetrable glass divide.

The introduction of Sissy, played by Carrey Mulligan, represents a sudden breakage in Brandon’s life and its cycles. Sissy, Brandon’s cloyingly named sister, breaks into his apartment. When he arrives at home, he is understandably surprised to find her in the shower. In this jolting scene, Sissy is naked, and we can see the hospital bracelet on her arm, but no mention is made of where she just came from. Further, there is no real talk of her history of self-abuse (which later becomes starkly evident) other than a single line: “When I was a kid I was bored.” We can see her naked body and hear fragments of her phone conversation as she tearfully begs an unseen former lover to take her back, but very little else is offered.

In a later scene, we find out she’s a singer, which takes us to a lounge bar at the top of yet another fancy glass building. Sissy sings New York, New York in a sheer dress, reminiscent of the one Marilyn Monroe wore when she sang Happy Birthday to JFK. She sings the song slowly and with uncharacteristic sorrow. It’s a paradoxically loud moment in an otherwise quiet film:

I want to be a part of it…

New York, New York

I wanna wake up in a city that doesn’t sleep

And find I’m king of the hill, top of the heap

These little town blues, are melting away

Midway through Sissy’s rendition, we realize something. This is not the glamorous, rat pack anthem made famous by Frank Sinatra. This is a song about a nobody stuck in a middle-of-nowhere town dreaming of a far off city and the success (and escape) it represents. New York, New York says more about McQueen’s central thesis for Shame than the majority of the preceding scenes. At its core, this is a film about desire. Wanting. More precisely, this is a film about wanting from the outside and desire’s central irony: that the pleasure of desire depends upon an object that can never be possessed. An object that can only ever be seen and yearned for and enjoyed from a distance. Manhattan’s iconic skyline cannot be appreciated from the city streets, and that’s why there are no happily ever afters. Because possession is a form of ruin. In life, but especially in capitalism, we are always desiring something that can never be fully spoken, let alone grasped and held.

Brandon’s apathy allows women to project whatever desires they secretly nurture, by withholding, by allowing himself to become the object of desire. The transactional quality of our modern world relies on pornographic thinking — utopic representations of a world without interiority and therefore without anxiety. According to Sontag, sexual desire is predicated upon a distinct flatness of character, exactly the sort of behavior boardrooms and casual dating reward. Put that way, Brandon’s sexual predilections are the only logical response to living in this type of society; it is somewhat understandable why someone like him might initially wish to lead a pornographic life. Advertising and pornography, alike, provide a respite from the tragedy of being human.

In a later scene, Brandon sees a couple fucking against the window of the Standard Hotel late at night. A voyeuristic moment, which he later attempts to re-enact with his maybe-girlfriend as their first sexual encounter. It doesn’t work out. As a matter of fact, we never see her again. Later the same night, he “succeeds” in recreating the fantasy, this time with a prostitute. Nothing fundamentally changes. Brandon can’t even sleep with the girl he likes because that’s not what sex means to him. Within the structures of capitalism, we are rewarded for being more machine-like, more fetishistic, more like Brandon. Sex is commerce; the commerce part is what makes it hot.

Addiction wreaks havoc and destroys lives. Society ensures it does. In fact, I think it is fair to say that our culture simultaneously cultivates the addict and shuns him as pariah — as social menace. But this is also what makes Brandon’s character scarily realistic and empathetic. Most of us have had at least a taste of what addiction feels like — the nagging desire to fill “the empty spaces,” to numb yourself. In the psychoanalytic sense, the condition of being human is not possible without wanting, without being and feeling somewhat incomplete and broken in the first place. Queer theorist Eve Sedgwick addresses this in her essay, Epidemics of Will. When discussing various notions of what constitutes an ‘addict’ (e.g. the alcoholic who tirelessly consumes; the anorexic who abstains), she notes:

We could argue… that what still unites the overeater, the anorexic, and the bulimic as substance abusers is, if not anything poisonous about the substance, still the surplus of mystical properties with which the addict/abuser projectively endows it; consolation, repose, beauty, or energy that can ‘really’ only be internal to the addicts themselves are delusively attributed to the magical supplement that can then — whether consumed or refused — operate only corrosively on the self thus self-construed as lack. In that case, healthy free will would belong to the person who had in mind the project of unfolding these attributes (consolation, repose, beauty, energy) out of a self, a body, already understood as containing them inpotentio

(Sedgwick 132)

There is a tinge of irony to Sedgwick’s words here. If addiction is a structure of desire, or, more accurately, a failure of ‘free will,’ we might ask what seems to be an obvious and fundamental question: Are subjects (social, political, thinking, sexual, etc.) ever fully free? The social subject is always in conflict with his unrecognizable aspects — his overflow. He is always in search of a more convincing repression. And therein lies the threat. This ‘shame,’ which McQueen implicates, is not particular to Brandon or the addict. It is a structuring of being and desire. The knowledge of what is forbidden, what could possibly subsume you, and also an imperative to both avoid and move toward it. Our bodies are always desirous, sites of potentiality and excess — always at the cusp of a conceptual chasm between sanity and disintegration. That’s why our skin, which pornography lays bare, is a site of eroticism and disgust. Flesh represents the libidinal borderlands between you and me, innards and air. The embodiment of our ever-present embodiment and fallibility.

Rather than engaging with Platonic ideals, Leo Bersani posits an interesting question in relation to this, “what if we said…not that it is wrong to think of so-called passive sex as demeaning, but rather that the value of sexuality itself is to demean the seriousness of efforts to redeem it?” (Bersani 222). We are always building our interior lives — always constructing and reconstructing ourselves as “whole” — finding ways to maintain the illusion, which perversity seeks to undermine. But it is this fact of ‘constructing’ which belies a fundamental lack. It is the self as project that erodes the ideal of a “healthy” person (or a ‘healthy’ sex life, for that matter). This is not to say that these are not necessary, protective mythologies, only that they are fundamentally unachievable if we are using this rubric of “completeness” and “dignity.” What McQueen’s film argues for is, therefore, not a politics of shame, but a politics of incompleteness and ir-redeemability. (Because anything else is a fantasy.) And, in that sense, Shame is uncomfortably and cuttingly true. That’s why Brandon is so unlikeable. He is too similar to all of us.

Shame dramatizes an ontological disturbance most of us would prefer to ignore. Being a human is an uncomfortable experience. In a way, we are all outsiders looking in, dreaming, and performing some version of “making it.” We all want to be a part of it. We all want to be at the top of the heap. But, ultimately, I think we reach for ‘dignity,’ for wholeness, and can only hope in vain to fully possess it. We are irreparably and shamefully lacking — always and already haunted by a sort of inescapable, insatiable need.

And there is nothing more relatable than that.

" alt="">

" alt="">