A child of the postmodern era, Tim Burton’s Beetlejuice (1988) is an ode to the unraveling of “good taste,” revealing American culture’s limits and contradictions with stunning sets and gauche character design. Set in an idyllic New England town, the film begins with the adventures of young newlyweds Adam (Alec Baldwin) and Barbara Maitland (Geena Davis), who want nothing more than to spend the holidays in their new country house. But, after a brutal car accident, the two find themselves dead and ghosted — prisoners in the very cottage that had once been a symbol for all their pastoral aspirations. The situation worsens with the arrival of the home’s new tenants: a bourgeois couple by the name of Deetz (Jeffrey Jones and Catherine O’Hara) and their goth daughter Lydia (Winona Ryder), on the run from New York City in search of their own version of quiet country life. Eager to expel the Deetzes, whose lifestyle is poorly compatible with theirs, Adam and Barbara end up contacting the erratically-dressed, erotomaniac, bio-exorcist Betelgeuse (better known as Beetlejuice), played by Michael Keaton.

In the opening scene of the film, as the camera swoops over Adam’s plastic model of their New England town, a spider forebodingly crawling along its surface, the viewer is left to wonder: Who is the real intruder? Who is the villain? Does the spider represent the ghosts, the Deetzes, or Beetlejuice himself?

At the end of the day, Beetlejuice is a black comedy based on the reversal of a horror cliché: in this case, it is the ghosts who want to get rid of humans. Created at the tail end of the 1980s, Burton’s film initially channels an undeniable distaste for New York yuppie culture, but the ultimate lesson of the story is much more complicated than simply demonizing metropolitanism. A critique of an American Bourgeoisie obsessed with the perpetual and amoral creation of capital, Burton first casts the enterprising Deetzes as intruders, even poltergeists, who must be exorcised.

Early in the film, Mrs. Deetz, a self-styled artist and her partner Otho are ready to renovate their new home into a kitschy, yet darkly surreal, playground. Their radical renovation transmutes a simple country cottage into a post-modern masterpiece — complete with a modernist take on a widow’s walk, monstrous sculptures, and shining, synthetic fabrics. Meanwhile, Mr. Deetz, a self-styled businessman, concocts a plan to transform the town into a renowned tourist destination. As her parents spiral outward with plans to transmute their surroundings into something resembling the very city they sought to leave, their daughter Lydia sulks, calling the life her family has created a “dark room,” which must be escaped by any means necessary. Thus Lydia, with her darkly cynical perspective, acts as a proxy for the audience. She is the only one who can see and, therefore, interact and sympathize with the phantom couple — even yearning, somewhat suicidally, to be a ghost herself. From there, a deep friendship is born.

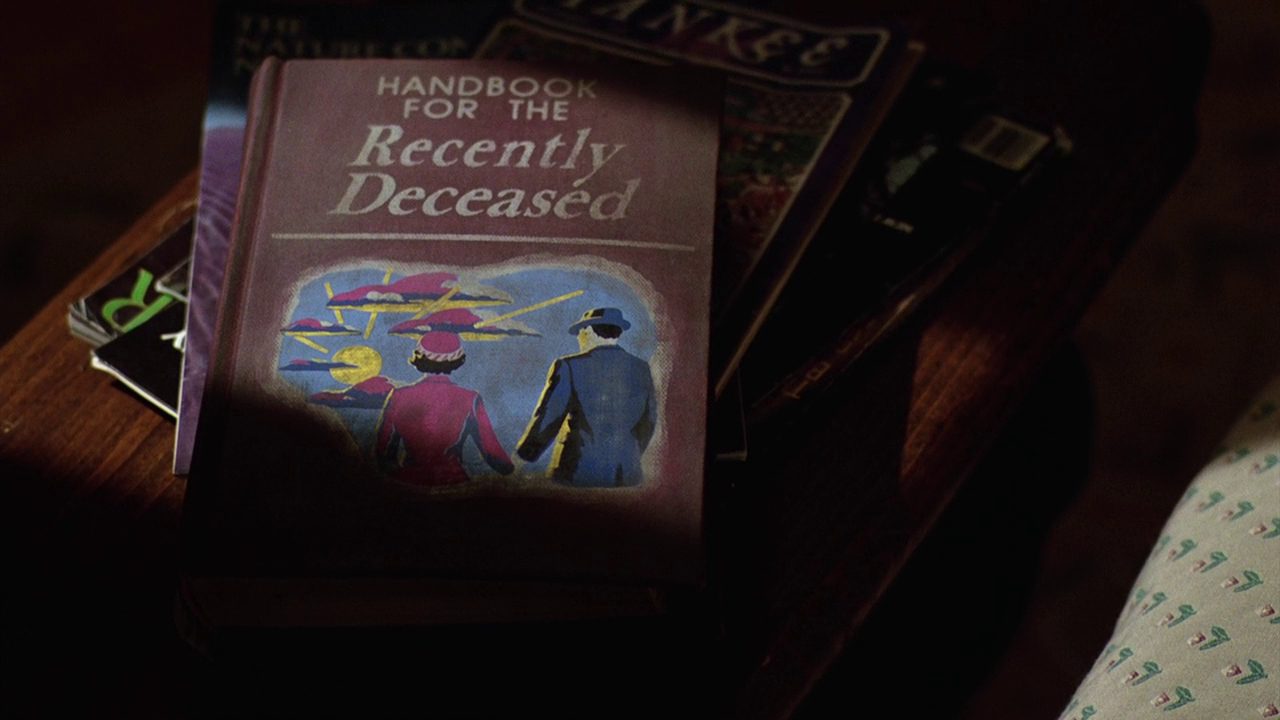

The comedic staging of “bad taste” in Beetlejuice ultimately reflects a society in crisis. Here, the search for supernatural experience seems to be the only salvation from an empty and superficial existence. For Lydia and audience members, alike, even Burton’s afterlife — a world that is as bureaucratic and horrible as it is colorful and fascinating — is a vast improvement upon the materialist world of the living. The grotesque and surreal aesthetics of Burton’s version of “hell” exalts the world of the dead into a colorful dreamscape.

Burton’s liberal use of special effects only emphasizes the blurred categories of living and dead, monster and non-monster. In Beetlejuice, true “monstrosity” belongs to those who “ignore what is strange and obscure.” Here, death and the supernatural represent an escape into the phantasmal — a phantasmal that is potentially horrible, but an escape nonetheless. And so, in Burton’s fantasy, the shadow world and the “real” world collide, the limit between life and death blurs, static objects animate, “good” and “bad” taste become interchangeable, and the sensibilities of urban life burst apart the pastoral imagination.

Despite this, the film reveals itself, finally, as a celebration of life and a hymn to hope. Eventually, the dead and the living find a way to live in harmony. Lydia dances in the air, lifted by supernatural forces, Mrs. Deetz decides to scare people with her sculptures inspired by Betelgeuse, and Mr. Deetz abandons his plans to transform the town into an amusement park. In the end, we even sympathize with the controversial character of Beetlejuice, who, for all his diabolical-ness, is basically a poor naïve prisoner, willing to do anything to get his freedom back.

A theme dear to existentialists, it is ultimately freedom that lies at the root of this film.

Each character wants to make use of it, to shape their own life and destiny as Adam does his play model of the town. Indeed, every character who attempts to grasp their version of “a peaceful life” ends up failing miserably. Because, for Burton, pastoral life in modernity is not a viable exit strategy. It is simply utopic thinking, (The very word, utopia, stems from the Latin root ou-topos meaning ‘no place’ or ‘nowhere.’) And, in this way, Beetlejuice serves as a reflection on reality and human existence. Life (and death, by extension) is a thing that is uncontrollable, strange, uncertain, precarious, and prone to failure. But there is beauty in the chaos, and in the fact that there is no real escape, and that is precisely what makes the work (and life itself) most authentic.

" alt="">

" alt="">