“I know of nothing better than the ‘Appassionata’ and could listen to it every day,” Lenin once told Gorky in reference to Beethoven’s “Appassionata” Sonata, before adding that he couldn’t listen to it very often because “it affects my nerves. I want to say sweet, silly things, and pat the little heads of people who, living in a filthy hell, can create such beauty. These days…you have to beat people’s little heads, beat mercilessly.”

This remark stuck in German director Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck’s head. What, he wondered, would have happened if Lenin had continued to listen to the “Appassionata”? He then saw in his mind’s eye the image of an officer from East Germany’s Ministry for State Security (otherwise known as the Stasi).

While Donnersmarck was born in West Berlin (with the “von” in his name signifying that he came from an aristocratic lineage, no less), and was only 16 when the Berlin Wall came down in 1989, he shaped from this image The Lives of Others. The 2006 film traces the spiritual reassessment and moral reconciliation of one Stasi officer who, while listening to his target play the piano, stops beating heads and starts patting them.

The scene plays out as a direct response to Lenin and Gorky: Playwright Georg Dreyman (Sebastian Koch) is woken up by an early-morning phone call. His friend (and, presumably, mentor) Albert Jerska, a director who had been blacklisted by the GDR’s overzealous censors, has killed himself. For Georg, an award-winning dramatist who counts among his friends First Lady Margot Honecker, this is his first real encounter with the idea that the regime that has nurtured his success has also destroyed the life of someone he holds dear. Early morning sun streams into the apartment; this issue is literally coming to light.

The scales fall from his eyes. Stunned, he sits at his piano and rifles through the scores, finding one that Jerska had recently given him for his birthday. “Sonata for a Good Man.” He starts to play. The music stirs Georg’s actress-girlfriend, Christa-Maria (Martina Gedeck) from the bedroom.

Georg speaks without turning away from the keyboard: “Do you know what Lenin said about Beethoven’s ‘Appassionata’? ‘If I keep on listening to this, I won’t be able to finish the revolution.’ Can anyone who heard this music—who really heard it—be a bad man?”

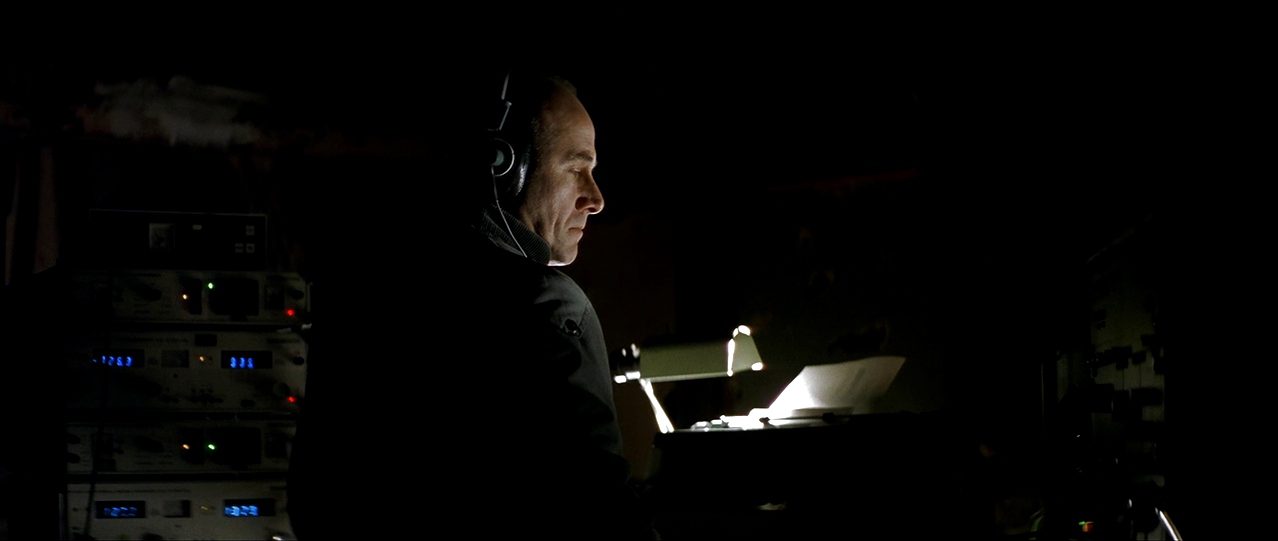

Also stirred by this is Stasi Captain Gerd Wiesler (Ulrich Mühe). Unbeknownst to Georg and Christa, Wiesler spends most of his days sitting in the attic space of their apartment building, monitoring them for the secret police. His charge is to find some damning evidence against the redoubtable Georg in order to put him away. It’s not that Georg isn’t following the Party line—rather, the East German Minister of Culture has been carrying on an affair with an unwilling Christa, and would rather not deal with the competition. But all of this is far from mind for Wiesler as the music begins. In the cold, drafty and dark attic space, he sits ramrod straight. He not only listens to the music, he hears something buried deep within it. Faced for what is likely the first time in his life with beauty, he’s beginning to realize the life he has lived in service of the State has been its own version of a filthy hell. His hardened expression begins to crack. A single tear rolls down his cheek.

Complementing the Leninist inspiration, as Donnersmarck notes in the director’s commentary for The Lives of Others, is Carl Jung’s theory of the persona: Every vice and virtue is contained within each of us. Who we are is simply the “mask” we choose to wear while we’re out in the world.

Donnersmarck instructed his actors to approach the screenplay (which he also wrote) with this in mind, in order to manifest Jung’s “inner drama of the unconscious.” As a result of this internal drama being rendered external, the masks that Georg and Wiesler have worn until now will begin to drop. Georg will write a dissident exposé of suicide in the GDR, published anonymously in western magazine Der Spiegel. (For this prop, Der Spiegel made a copy of the magazine with this as a cover story, explaining to Donnersmarck that “it’s a story [they] should have run” during the Cold War.)

And, when authorities suspect Georg of being behind the editorial, Wiesler covers for him. He falsifies reports, covering up for Georg’s meetings with colleagues and editors as preparations for writing a play (based on—what else?—the life of Lenin) and even going so far as to remove a contraband typewriter from his apartment before his comrades can find it.

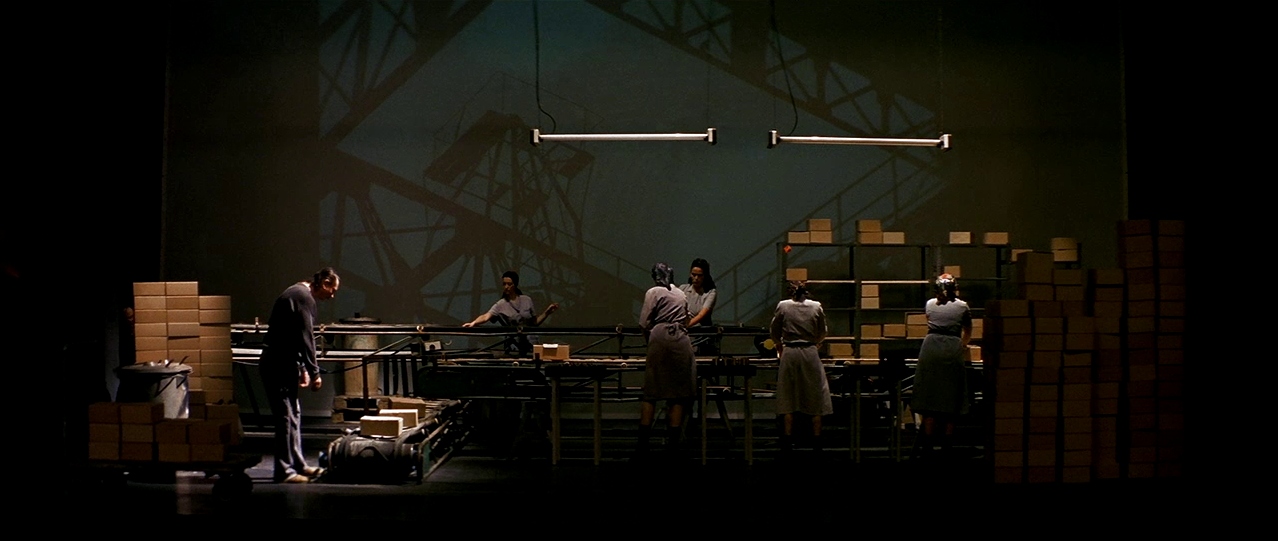

Donnersmarck emphasizes that these changes are internal through Gabriele Binder’s costumes for both Georg and Wiesler. Until The Lives of Others transitions into a reunified Germany, Georg wears the same brown corduroy suit and off-white button-down shirt for much of the film’s 140 minutes. Only in the “Sonata for a Good Man” scene does he wear something else (his pajamas, a dark grey shirt and white pants). Playing into cinematographer Hagen Bogdanski’s atmosphere of Brechtian grey, the actors are left to produce their own warmth against a palette that captures the concrete-and-steel essence of the GDR.

Interiors play a major role in The Lives of Others. Like many Germans who grew up before the fall of the Wall, Bogdanski recalls that the streets of East Berlin, “were very dark. Everything was happening inside, in private.” With its rich browns and peeks of green, Georg and Christa’s apartment, therefore, cultivates a haven against the horrors of history, the artistic life of the mind. Georg’s peat-brown corduroy and ecru cotton is both a suit of armor and a nod to the natural world that contradicts Soviet industry.

Wiesler’s home and wardrobe, by contrast, are all cool greys and synthetic materials, showing how underexplored his own unconscious is. He wears a nylon windbreaker that is all shades of grey almost like a straight jacket when he isn’t in Stasi Headquarters. While Georg’s suit seems at times to hang off of him, Wiesler’s jacket is folded around Ulrich Mühe’s frame like hospital corners, zipped up to his chin. He is unbending, unflinching. The jacket begins, however, to hold all of the tension Wiesler accrues on this particular assignment. He readily, invisibly, guides Georg to discover his girlfriend’s affair with the Minister of Culture (“time for some bitter truths,” he mutters as he plays the invisible hand).

But as he spends more time with these two artists, he begins to wonder why either can be considered even potential enemies of the state. He enters their apartment at one point, almost as if trying to find clues to their life. How are they able to live seemingly full, authentic lives while he isn’t? As Donnersmarck explains in his director’s commentary, Wiesler then has to struggle to accept that he cannot be like these artists. With this growing realization and internal conflict, the jacket seems to grow more and more suffocating. By the time Georg confronts Christa over her infidelity, Wiesler seems pained, suffocated between his jacket and his headphones (which Donnersmarck took half a day to “cast”).

Wiesler leaves his shift shortly after Christa leaves for her rendezvous, unsure of where to go from there. Stumbling along a side-street, looking off into space, a drunkard slurs at him, “What’re you staring at?” He ducks into a bar. Unzipping his jacket, letting down his own armor, he asks for a soda water and then changes the order to a vodka. Double. When Christa enters a few moments later, ordering a cognac before her State-mandated droit du seigneur, Wiesler turns from being a passive observer to an active participant in the lives of his surveillance subjects. His jacket is open, as is his soul.

“Many people love you for who you are,” he tells Christa. “Actors are never ‘who they are,’” she responds, her sunglasses still on despite being indoors at night. As he sits down, he insists that she is. He’s seen her onstage, where she was more who she is than in this moment. “I’m your audience,” he says—a meaning that cuts several different ways.

Christa is skeptical, but curious. She lowers her sunglasses. “So you know her well, this Christa-Maria Sieland. What do you think… would she hurt someone who loves her above all else? Would she sell herself for art?”

“For art?” Wiesler asks. “You already have art. That’d be a bad deal. You are a great artist. Don’t you know that?” This is enough to convince Christa to stand up her date. She gathers her glasses and her giant fur hat. “And you are a good man,” she says as she rushes out the door, back to her home and the man who loves her above all else.

As both Georg and Wiesler become more consciously, aware of the multitudes their souls contain, their costumes continue to show signs of these changes. They lose their armor as they lower their masks. When the Stasi raid Georg and Christa’s apartment, after Christa crumbles under interrogation, Georg’s suit goes from appearing warm and professorial to wrinkled and disheveled. His armor breaks down as his life begins to fall apart. Wiesler’s career, tracing a concentric path, does the same as his colleague realizes that he is the one who saved Georg at the expense of the State.

While the central story, Wiesler’s transformation is one of the larger points of criticism levied against The Lives of Others. “No Stasi man ever tried to save his victims, because it was impossible. (We’d know if one had, because the files are so comprehensive.)” writes Anna Funder, the author of Stasiland, who describes the film as a beautiful fiction covering an ugly truth.

Musician and former East German dissident Wolf Biermann (who was stripped of his citizenship in 1976) concurred in a separate response to the film. “If such Saul-Paul conversions of Stasi officers really did take place, where were similar shining examples after the fall of the Wall?” But amid the uncertainty and suspicion of this act of fiction, he also enjoyed the film, concluding, “I cannot know whether the wonderful conversion of the Stasi chief is a historical lie or an artistic understatement. We are all addicted to evidence of people’s ability to change for the good.”

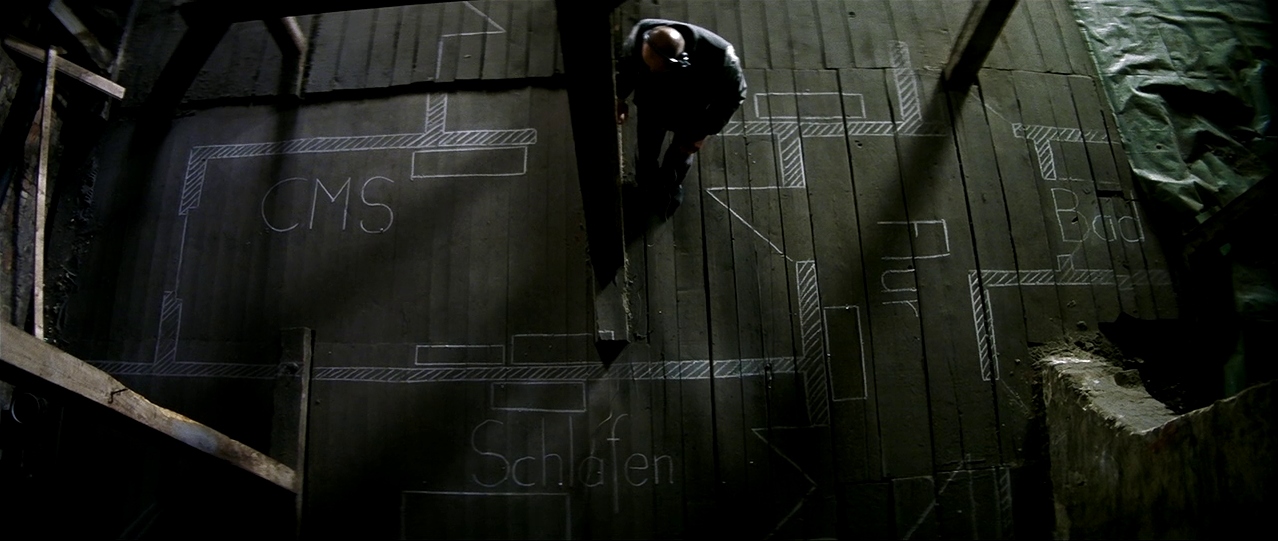

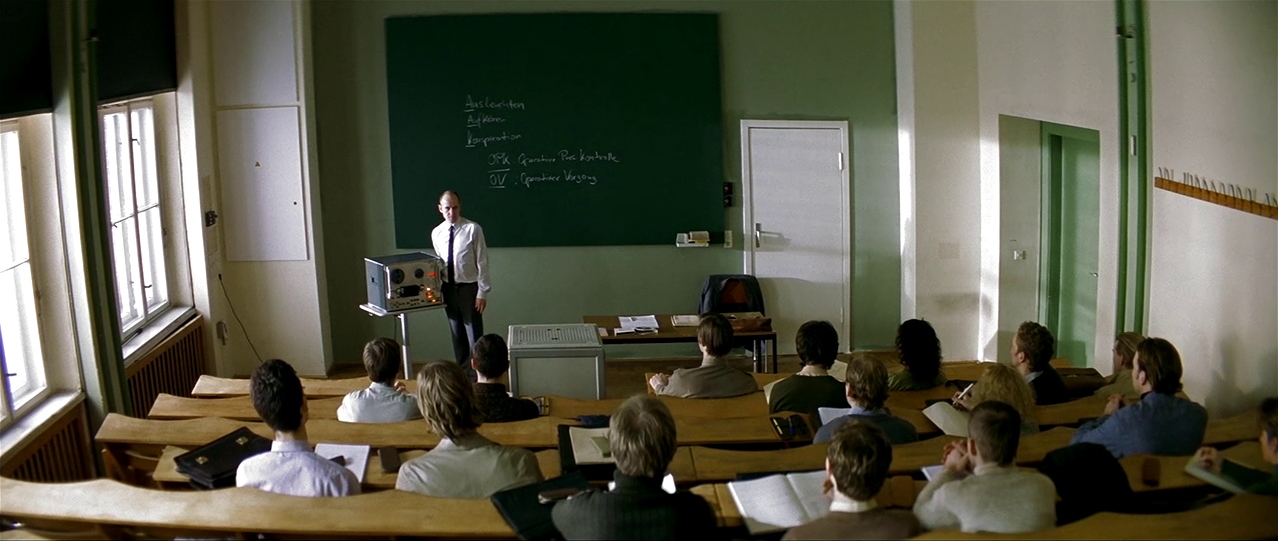

In the case of The Lives of Others, the act of watching people watch the movie through these reviews and reflections becomes an essential part of engaging with the film, which matryoshkas itself with layers of watching and being watched. The film opens with Wiesler interrogating a man in Hohenschönhausen Prison. What the prisoner isn’t aware of is that his interrogation is being recorded by Wiesler. Wiesler will then use that to teach a group of students so that they may interrogate others.

Wiesler, in turn, is being observed in this scene by his old friend and classmate, Anton Grubitz (Ulrich Tukur). Grubitz then invites Wiesler to the theater to see the premiere of Georg’s new play (and to brown-nose the Minister of Culture), which becomes another scene of observers and the observed. Through a pair of opera glasses, Wiesler watches Georg watching his play (which begins with Christa’s character having a clairvoyant vision).

Very rarely, however, do the characters observe themselves. As Jung writes in The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious, “The mirror does not flatter, it faithfully shows whatever looks into it; namely, the face we never show to the world because we cover it with the persona, the mask of the actor.” Christa wears her sunglasses to avoid facing herself, even in the dark of night.

In an earlier scene, Georg and Christa are readying their apartment for his 40th birthday party. Christa, glamorous in a black velvet dress (her costumes, while treading the same territory of neutrals, are the most varied), reminds Georg that he promised to wear a tie for the evening. He would, he replies, but he doesn’t own one. Of course, she’s bought him a tie for his birthday.

“You said you didn’t want any books,” she says. “Or can’t you tie a tie, you old working-class poet?”

“What? I was born wearing a tie! I had to ‘fight my way out of my middle-class fetters.’”

Christa asks Georg to put those fetters on again, just for her. But in the entryway mirror, he’s confronted with his own shortcomings as he tries to make a simple knot — and fails miserably (while also subtly hinting at the image of a noose that would soon claim Jerska). Fortunately, Georg’s neighbor, Frau Meineke, is coming home at that exact moment. He opens the door and beckons her in. She’s nervous and taciturn—she saw Wiesler and his colleagues bugging the apartment, and was warned at the point of her daughter losing her place in university to tell no one. But she can tie a tie. Perfectly. Georg admires her work in the mirror, which she avoids looking in.

“It’ll be our secret,” he whispers to her. “You can keep a secret, right?”

“Of course,” she says abruptly, retreating back into her flat. She’s unable to look at herself in the mirror. (“People will do anything, no matter how absurd, to avoid facing their own souls,” writes Jung in Memories, Dreams, Reflections.)

After the Wall comes down in Berlin, Georg—who has been unable to write since that event—learns that his apartment had been bugged. Shortly after, he goes to the Stasi Archives, which were opened to the public following the fall of the GDR. It is then that he learns about the full scope of surveillance he was under for five years. It’s here that he discovers the inconsistencies in his reports—the plot of the Lenin play, a telltale fingerprint—and realizes that he had been saved by the man who had been sent to bring him down. He realizes once more that we contain multitudes.

In learning Wiesler’s identity, however, he can’t bring himself to connect with the man who is seemingly his double. The most he can do is observe him through a taxi window as Wiesler now makes his rounds as a mail carrier (the observer becomes the observed). He has a new jacket, still an icy-cold grey, but one that gives him a bit more room to move around in. He still believes that the world he’s craved since his exposure to Georg’s life isn’t for him.

One year later, Georg has published a novel, Sonata for a Good Man. We discover this along with Wiesler as the camera pans a bookstore window. Wiesler goes in, opens the book. It’s dedicated to him, “in gratitude.”

His face betrays very little emotion, but he goes up to the counter with a copy. When the clerk asks if he’d like it gift-wrapped, Wiesler responds, “No. It’s for me.”

Another mask falls.

" alt="">

" alt="">