1987 in New York City. There’s a breeze coming down 5th Avenue on your 8 pm walk home from work. It’s Tuesday night. Paul Simon’s “Graceland” starts on your Walkman as you wait at the corner for the light to turn. A man joins you; 6 ft. tall, even tan, nice hair, his suit fits well, and those suspenders look good. He gives you a side smile and you return the glance. “Do you like Huey Lewis and News?” he asks. Things are good, what a time to be alive. Until you’re not.

Mary Harron’s psychological horror American Psycho is a disturbing filmic accompaniment to Bret Ellis’ 1991 novel. Wall Street businessman by day and unrelenting serial killer by night, protagonist Patrick Bateman (Christian Bale) spends his time among the young New York elite attending trendy restaurants, flaunting business cards, and perusing the streets for blond prostitutes whose heads might look nice in a freezer next to the sorbet. Most importantly however is his regimented skin care routine, and curating a music collection that features the latest from Phil Collins and Whitney Houston. Hiding his alter (psychopathic) ego from the likes of his self-absorbed coworkers and fiancée proves no difficult feat, and with a simple “I’ve got to return some videotapes” Bateman gives himself an out in every situation.

A postmodern cult classic, Psycho is particularly successful in the way it reveals the subtleties of the female gaze. The film resists the novel’s anti-hero allure, focusing rather on Bateman’s grotesque bloodlust, sexism, and obsession with his own image. Psycho’s satire comes from an emotional nihilism, and Harron translates this facet of Ellis’ text into a treatise on the superficiality and vulgarity of male entitlement. Harron’s camera work is intentional as it lingers on Armani ties, Valentino suits, and Oliver Peoples glasses, exposing the banal decadence of these Wall Street men. Condescension is a must, as are pinstripes and an AmEx. No one in Harron’s film escapes the monotonous, yet quintessential, 80s fashion details, as each male character dons a humorous uniformity from the low gorge lapels to the tips of his long jacket. It’s all an act, and every man — killer or banker — proves the same.

In one of the film’s most famous scenes, Bateman sits at a conference table with his colleagues where the men tend to a very pressing matter: their freshly printed business cards. Tensions are high as the young stockbrokers contest one another like roosters in a cockfight over fonts and coloring. Bateman has an internal crisis about whether his Silian Braille font matches up to Van Patten’s Roman; should he have gone with Eggshell or Pale Nimbus rather than bone?

Paul Allen’s card is by far the most impressive and Bateman, in his envy, is barely about to croak out a response. Allen (arch nemesis in swagger) often mistakes Bateman for “this dickhead Marcus Halberstram,” but this is no surprise, as Halberstam does the exact same job as Bateman, and shares a proclivity for Valentino suits and Oliver Peoples glasses. His haircut, however, as Bateman reassures us, is slightly worse than his own. The men are carbon copies of one another, distinguishable only by marginal differences in material taste. Even when the camera focuses on Allen and Bateman, their identical glasses and styled brown hair imitate one another, almost as if they’re each staring into a mirror.

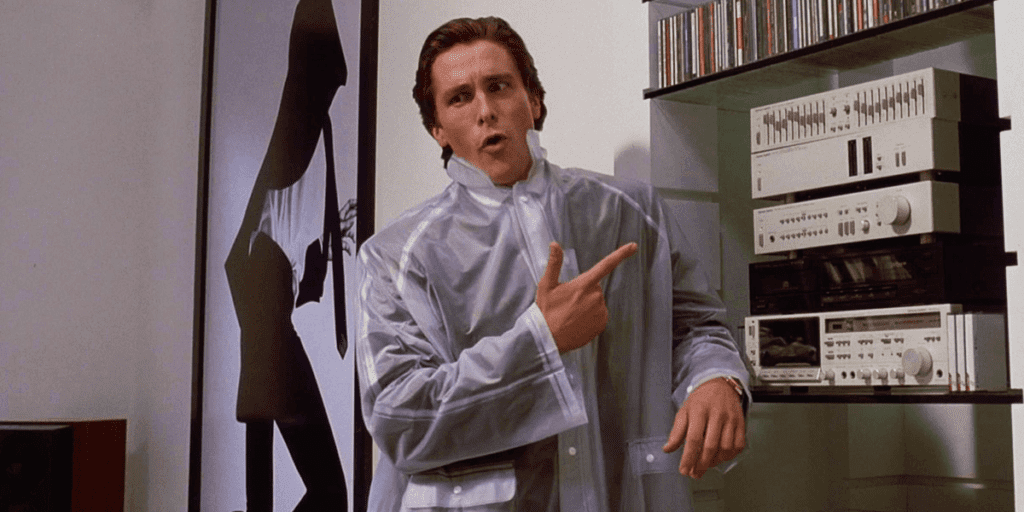

The impressive watermark on his business card ultimately proves fatal for Allen, as Harron gives us the first insight into Bateman’s psychopathic after-dark charades. After dinner, the two men return to Bateman’s apartment which is lined with newspaper and plastic wrap. Bateman dons his classic translucent raincoat, indicative of transparency and superficiality. There is no time for small talk when Bateman ends a comically upbeat rant about Huey Lewis by lodging an axe in Allen’s head. The camera pans outward with Allen’s legs foregrounding Batman who sits center screen lighting a cigar while “It’s Hip to Be Square” plays loudly. The pinstripe grey pants that a now-dead Allen wears match exactly those of his killer. This similarity, paired with the song’s lyrical subtext, adds a sardonic flair to the scene, as Harron posits the vile repercussion of male uniformity and ultra-narcissism.

An important aspect of Harron’s film is the grotesque correlation between masculine libido, female objectification, and extreme violence. One evening, Bateman is joined in his apartment by two prostitutes. Christi, as he prefers to call one of them, dons Batman’s bathrobe after he has made sure that she is properly cleaned in the bathtub. Stripping her of her individuality, Bateman dresses the woman in a piece of his own clothing to illustrate both his dominance and to evoke a sense of ownership. The other woman, clad in black lingerie and high heels, gives us the stereotype call-girl impression to satisfy the masculine ideal.

Particularly interesting are the camera angles during the threesome’s interactions; Bateman is often placed at center screen between the women. Their backs are turned away from the audience while the banker spews lines about Phil Collins. In this way, the audience adopts the gaze of these women, focused on the narcissistic man who has bought their attention. Further, when matters are taken to the bedroom, a naked Bateman stares at himself in the mirror — the front camera — with only a woman’s legs propped on his shoulders in the frame. The high heel (a male construction of feminine sex appeal) in contrast with Bateman’s self-absorbed reflection composes a fascinating correlation between female sexuality and male entitlement. Bateman’s sexuality is entirely narcissistic, centered upon a pornographic infatuation with… himself.

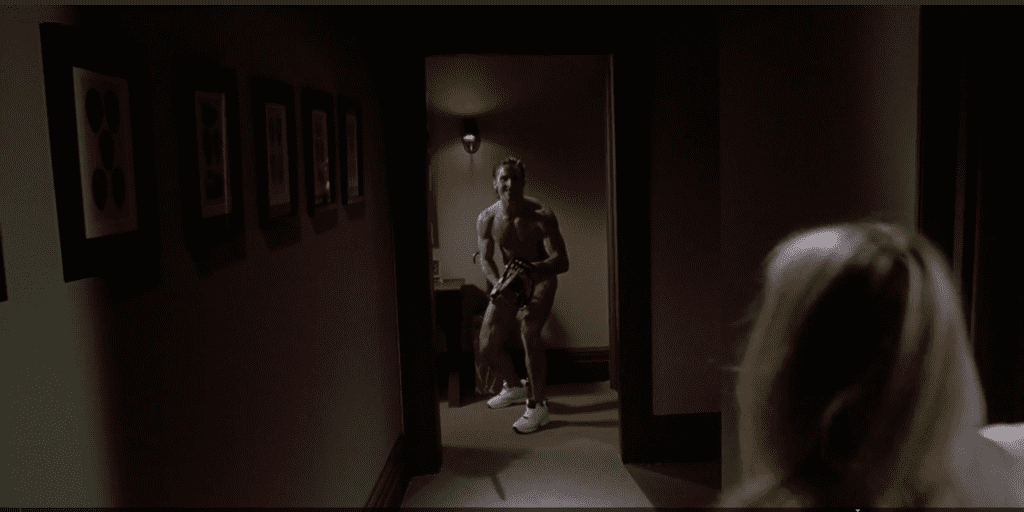

After a violent interlude that takes place off-camera, Christi reluctantly returns once more to Bateman’s apartment, a decision she soon regrets. The scene culminates when Christi, dressed in a white nightgown, runs from a naked, hysterical, and blood smeared Bateman with a chainsaw in his hand. Despite this scene’s abhorrent, if not terrifying, content, Harron composes this shot quite humorously. Here Harron plays with the archetypal serial killer narrative, including all the proper elements of a good horror film. Bateman wears large, white, designer sneakers, which he apparently took the time to put on before chasing a woman to her death. Without his Valentino veneer, Bateman’s true nature is exposed to the audience. Christi, dressed in white, adopts the righteousness of the female gaze, a classic horror movie victim.

Ellis’ novel is written from Patrick Bateman’s perspective. The book is his mirror, an ode to Bateman’s violence and power. But Harron interprets the vile world of Patrick Bateman through a very different lens. She turns the tables on Ellis’ unreliable narrator, ultimately highlighting Bateman’s absurdity and impotence. His façade breaks under Harron’s unblinking lens, as she successfully wields the nuances of the female gaze to mock and expose him.

" alt="">

" alt="">